How to plan and write serial fiction using Scrivener

The low stress way to write a long-form story

Writing software Scrivener doesn’t make me a better writer. But it does make it possible for me to write in a particular way. Without it, I’m pretty sure I’d have suffered one of these fates:

Burnout: writing a weekly serial is hard. It requires constant production, so the risk of overloading is very real. This would be bad. Instead, I’ve written and published three back-to-back novels in serial form and am currently in the thick of my fourth.

Extreme stress: even if I was able to keep up with the schedule, without Scrivener I’d be a blubbering mess in the corner of the room. I wouldn’t enjoy the process of writing, which would inevitably result in me writing less over time. I don’t believe in the necessity of the ‘suffering artist’. It’s absolutely possible to create and be happy and healthy.

Narrative structural collapse: without Scrivener, the most likely scenario would have been me getting in a complete muddle, falling into plot holes, running into writer’s block, contradicting myself, losing the pacing and so on. The stories wouldn’t be as good, and readers wouldn’t be confident in my abilities as a storyteller.

When I tell other authors that I write and publish a new chapter of work every single week, and that I’ve done so across four separate books and 9 years, they quite often look at me like they’ve just witnessed the gibberings of a madman. Often the question is simply…but how?

I suspect the answer is…well, Scrivener.

Important Note: This is going to be a very deep dive into my process of writing a long form serial. You will absolutely, positively want a cup of tea for this one.

If you haven’t heard of Scrivener and are wondering what I’m on about, hop over to my intro video before reading any further:

Scrivener is useful for any long form project, but it’s especially well suited for anyone working on a serial (fiction or non-fiction). That’s because Scrivener’s feature set is heavily weighted towards structure. I’ll get into the specifics in a moment.

My stories tend to be lengthy, with large ensemble cast. There are subplots and multiple story strands that have to be woven together. My particular publishing process is to write and publish as I go, week-by-week.

It sounds very seat-of-the-pants, but I’ve always enjoyed the process and have rarely felt stressed by it. I’ve also never missed publishing a week’s chapter (unless it was on purpose, such as taking an actual holiday).

I am convinced that I wouldn’t be able to write and publish like this without Scrivener.

I’ve written about the way I plan my stores in the Story Loom post:

My layered approach is to start with the basics and then peel away to discover the details. The entire book could be summed up in a single sentence at the start of the process, but that’s not going to help me write the thing. Ideas documents need to be translated into practical, working plans, that can then be magicked into actual words on the final pages.

If I’m writing chapter 5, I’m simultaneously planning chapters 6-10 in fine detail, as well as laying out chapters 11-20 in looser detail. I’ll also have an eye on chapters 40-50 and the final ending, as well as those key milestone along the way. It’s like navigating through an unfamiliar place with a map, except I’m also the person responsible for drawing the map.

My approach to writing serials — especially my current one, Tales from the Triverse — often feels closer to television storytelling and production than it does to novels. One episode is in pre-production, another is shooting, another is in post-production. Another has been sent off to the audio department, or to VFX.

Juggling all of that is made immeasurably easier by using Scrivener.1

Step 1: Early development

Here’s what my Scrivener binder looks like:

The ‘binder’ is a collection of documents, but all contained within a single project.

Up the top, inside the manuscript folder, is the book itself. Each of those sub-folders represents a chunk of the book. Think of them like seasons of a TV show, or parts of a novel. Inside of them are the actual chapters, but we’ll get to that momentarily.

Ignoring front and back matter,2 we then have three critical sections: Characters, Places and Research. I don’t tend to use the Notes section.

Most of the up-front pre-production effort goes into Research. This is where all of the world building, backstory and primary plot stuff is worked out:

As you can see, it's quite the hodgepodge of stuff.

I always prioritise characters and actual story over lore, but in the case of Triverse it was important to get a lot of that worked out ahead of time. Triverse is primarily a detective thriller, and if the police were going to be working on cases I had to define the parameters of the more sci-fi and fantasy elements, otherwise it wouldn’t be fair to the reader. I couldn’t make it up as I went along, because that would ‘cheat’ the investigations.

Hence in side the ‘Lore’ folder you’ll find this:

Everything I might need to know or reference. In fact, each of those settings has further detail:

Those seven aspects of the world — tech, economics, religion, geography, culture, politics and language — were the bare minimum I needed to understand the places. Once I’d defined each of the worlds I was ready to start figuring out the actually interesting stuff, like character and theme and story.

Remember, this is all happening inside a single Scrivener project. I don’t have tons of Word docs floating around, or separate notebooks and sticky notes. It’s all in one place, and can be easily referenced. Even now, over two years into the serial, I can easily pop up the fantasy world’s ‘technology’ article to remind myself of pertinent details.

It means I don’t have to hold all this information in my head, and I don’t need to go hunting for it when I need it. It’s always at my fingertips.

Step 2: Planning and plotting

“Multiple folders of indulgent world building is all well and good, Simon,” I hear you say, “but we’re not playing D&D here. We’re not editing a fan wiki. Where’s the actual novel?”

It’s OK, we’re getting to that. Once the world building reached a critical point, I had enough detail to start working out what would actually happen. I still have the early documents from Triverse’s development, from summer 2021, such as:

Each chapter is a new case, following a different officer. Characters overlap, as it’s a single department. Can have fun with assumptions and reactions based on the subjective narratives of each character.

Should a season cover a whole year?

Each case is 2 chapters?3

Open with a cast list (with pics/sketches?)

5 cases per season?

The plot begins as stream-of-consciousness-style documents. For Triverse I split it down into various strands:

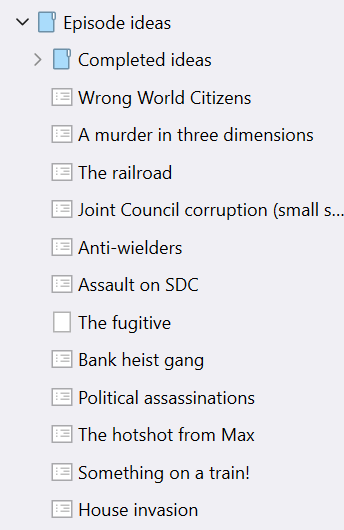

The episodic nature of Triverse meant that I could jot down ideas for individual episodes separate to the main arc of the story. These episode ideas could be pulled out one-by-one and inserted into the story whenever made sense. This is very unique to a more anthology-structured story and isn’t how I’ve worked out my earlier novels. It’s been a fun way to work, though!

The list continues below that screenshot. Some of the ideas will never make it into the series, which is fine: but having a surplus of individual episode ideas means I’ve never had to worry about running out of things to write.

Due to the way Scrivener works, I can drag any one of these ideas from the research folder into the ‘Manuscript’ folder, at which point it becomes part of the actual series. I can use this to insert placeholders for upcoming chapters, and continue to shuffle them around to best suit the needs of the story. The manuscript chapters end up looking like this in the binder:

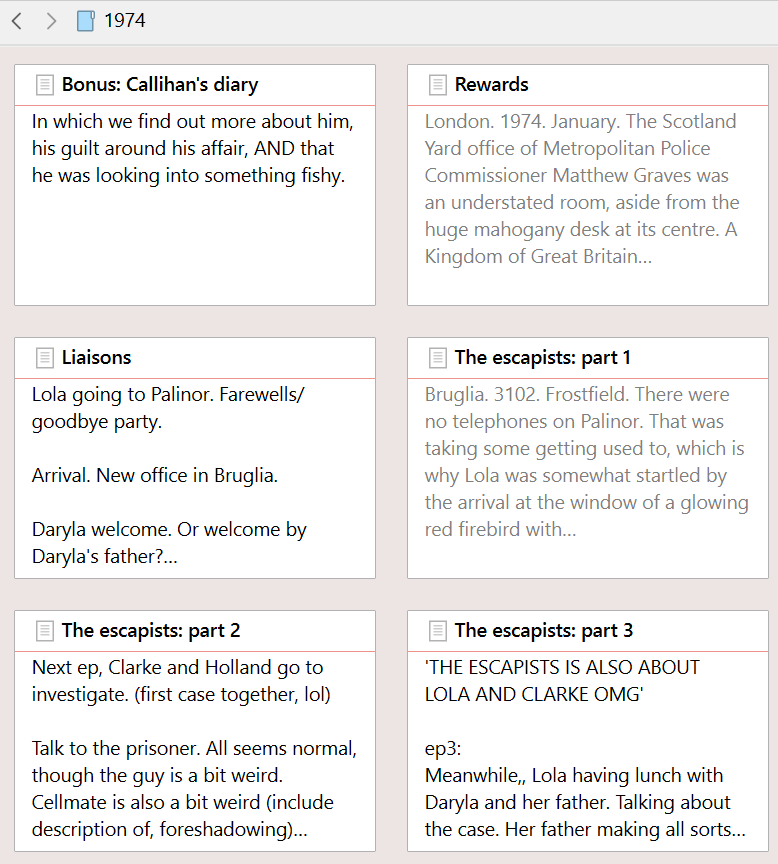

The binder isn’t the only way to view your documents in Scrivener. When wrangling a large section of story I’ll often switch to the corkboard:

This is more like moving around post-it notes on a whiteboard. See that all caps bit on ‘The escapists: part 3’? That’s me shoving a spur-of-the-moment note about the story into that chapter’s overview, so that when I came to write the thing I wouldn’t forget. In Scrivener a chapter has the main text, of course, but it also has a ton of metatext around the edges, where you can keep notes and keep things organised.

The ‘synopsis’ panel is where I do a lot of my thinking, week-to-week. Sometimes it’ll be a single line descriptor, like this one for the early chapter ‘The koth: part 2’:

The SDC track down the koth. It is killed during a fumbled arrest attempt.

Other times it’ll be a world building element specific to that chapter, such as this on the first part of ‘The creature’:

Creature has a life-cycle.

Rapid growth, but starting very small.

Begins increasing threat.

It is not native to the Mesa area, but came from a zoo/menagerie in Bruglia. A tear opened up and the egg fell through.

They are rapid-growing creatures, and the poisonous atmosphere in Mid-Earth London seems to accelerate it.

Larvae

Lizard thing, dog-sized

Pony-sized, six legs

Horse-sized

Rhino-sized, two middle legs start shifting into raised positions

Small elephant-sized, middle legs start growing with membranes. Can climb.

Large elephant-sized, wings now operative for gliding.

Larger-than-elephant-sized, can fully fly.

There’s little plot detail in there, because that first part was mostly an atmospheric piece.

Sometimes I’ll have chunks in the notes that are discarded. Each week I’m reacting to the previous as well as what’s coming up, and in-between writing sessions is often when the best ideas surface. Hence this bit from ‘Immortality: part 3’:

==NOPE==

3. N & Z go to Lazarus' operation. Fancy shop on fancy street. Super expensive holiday trips, with promises of longevity treatments.

Eye waterin sums. Only available to super, super rich. They're happy to lose it all to try to keep it all.

Meeting of the group at the old base.

4. Lola and Just Enough receive messages, asking about the treatments. JE confirms it's a fake clinic. Lola isn't sure, as it's far beyond Bruglia's borders. (does Lola go off on a journey? probably too much). He's arrested for fraud, but it also turns out that Lazarus IS really old.

==ALL NOPE==

Some of the synopsis notes read like me having a mad conversation with myself. I’m rubber ducking the plot and character problems, and in the process of writing out fiddly aspects or plot holes or road blocks I usually end up figuring out a solution.

Point is, Scrivener is as much project manager as it is word processor.

Step 3: Doing some actual writing

Let’s not get distracted. None of the above is any good if I don’t get the actual words down. A risk with something like Scrivener is that you can spend so much time faffing about organising everything that you run out of time to actually do the thing.

This, basically:

The actual process of writing in Scrivener is very simple. The text of a document works like any other word processor, with the usual tools at your disposal. Here I have my notes open on the right, and I can easily hop to other parts of the project using the binder on the left, but my focus is in the middle:

If that’s still too much, there’s a handy writing mode that strips away all other distractions:

In that example I still have my notes open, but I could close those and have an entirely clean writing experience. If you struggle with keeping your attention on the words, it’s really useful.

Something else I find useful is this little fella:

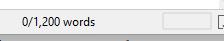

You can set targets for the document (as well as for individual sessions and the project as whole). I have 1,200 words as my typical chapter length, so I tend to set the target up when beginning a chapter. This then manifests as a word count and progress bar at the bottom of the document:

The bar gradually fills up until it turns green:

1,200 words is the sweet spot for me, because it’s relatively easy to accomplish. I also find that even if I’m not really feeling it during a session, if I manage to get to 400 words I’ll often carry on to completion. The progress bar has a lot to do with that, as it changes colour towards green. It’s a little nudge of encouragement.

Step 4: Post-production

Once the text is done, I move into the editing phase. Although, to be more accurate, I’m never not in the editing phase. I edit as a I write, continuously tinkering and changing sentences and word choices. This helps make the first draft relatively decent, because it’s been through several passes along the way. Writing on a computer really helps my process here, as I’m able to remain very fluid in the writing. If I was writing freehand with a pen and paper my text would be indecipherable even to me.4

First up is a quick spellcheck with Scrivener’s built-in system. Basic, but spots any glaring typos. I don’t personally use Grammarly or any of the other automated systems for my fiction, but if they speed up your process by all means go for it. Just make sure you don’t let them start to homogenise your writing style.

A major part of my editing process since the start of 2024 is incorporated into my creation of the audio version. Reading your work out loud is a superb way to perform an editing pass, as it transposes the work into a different form and makes it far easier to spot errors and potential improvements. As I record the audio narration I am also editing, fixing problems and tweaking any clunky sentences. I’ll pause in the recording, make the changes, then re-read the improved section.

The amount of editing varies depending on the chapter. Some require more extensive retooling than others, usually when there are complicated story or character beats occurring, or if the chapter is dealing with sensitive topics that require extra attention. I don’t tend to redraft, though: the published chapter is the first draft with several layers of enhancement, rather than an entirely new second, third or fourth draft.

The final checks come when I plug it all into Substack for publishing. That’s another chance to see the work in a new context and fix any last-minute issues.

Step 5: Go to step 1

Remember, while I’m writing one chapter I’m usually planning what’s coming up imminently as well as kneading the long-term plot. There are lots of spinning plates at all times.

The key thing is that this very rarely become stressful. I really, thoroughly enjoy the process of writing an online serial, and of writing ‘in public’ in this form. In large part this is due to my use of Scrivener. It makes a project on the scale of Triverse possible without my mind breaking. I feel secure in the storytelling, because I can see it all laid out before me clearly.

Of course, you don’t have to use Scrivener. You may well be doing all of this using other tools, digital or otherwise. It’s always worth reiterating that it doesn’t matter what you use, as long as it works.

Writing a serial, and remaining a happy writer, is often about getting the process right. ‘Writer’s block’ isn’t always to do with the writing itself, but all the complications around the edges. Scrivener, for me, clears away all of those obstructions. It takes care of the technical difficulties of writing fiction, so that I can focus on the creative challenges.

Thanks for reading. That was deeply nerdy and very long. If you’re still reading, I can only apologise.

If we’ve got this far we might as well keep going. Over the weekend I bunged up a bunch of tips for recording voiceover which might be of interest to anyone thinking of doing the same:

I’ve been seeing a lot of new serial fiction writers popping up on the scene of late, which is very exciting indeed. When I started doing serial fiction via newsletter back in 2021 it was a bit of weird thing to do and there were only a handful of us making much noise. That’s no longer the case: more writers and, crucially, more readers are showing up all the time.

In fact, shall we say hello?

If you’ve just started publishing your own serial, do drop a link down in the comments.

And if you’re not sure whether writing serial fiction is for you, my nuts-and-bolts how-to guide might be worth a look:

How to write serialised fiction

This is a 22 chapter rough guide, taking you from understanding the core form of serial storytelling, through plotting and themes, character creation, plot twists and much more, all the way through to hitting the ‘publish’ button. There’s even a chapter all about how to cope when people say nasty things about your writing.

OK, this post is already absurdly long, so I’ll leave it there.

Thanks again for your time and support. It means more than I can express in words, which I suppose makes me a bit of a failure as a writer.

It doesn’t have to be Scrivener specifically. Other software is available, and you could do a lot of those non-digitally, too. Scrivener is the thing for me, though.

Those are useful when compiling ebooks or manuscripts for print.

Clearly, I didn’t keep to this. Ahem.

It would also slow me down too much. I can only work at the pace I do by working digitally.

I've been using Scrivener for eight years now through roughly ten books, and I honestly can't imagine going without it at this point. Just being able to jump between chapters at a glance within one document was an immediate game-changer. Then you add in the other features and it just rockets past any other writing program or word processor.

Thank you for the deep dive. Insightful and fascinating to see the layers of your process. I know it’s not a writing tool per se, but I’m just starting to play with Notion to see if I can create a writing system in there with research, notes, main writing, etc. we’ll see.