Cultivating a healthy reader community

Or: What to do when Emma Horsedick comes a-riding

Today’s newsletter is part of my Substack for Beginners series. The concepts might also be useful for other platforms. Customise what’s in your inbox here.

Putting your head about the parapet is a risky thing. As humans we have a built-in hesitation to do so, for fear we’ll be spotted and attacked. Millennia of ingrained self-preservation is hard to ignore.

If you’re a writer, and especially if you publish online, you’re voluntarily announcing yourself to the world. It’s an invitation for strangers to read your work, and how they will respond is hard to predict. Whatever it is you’re writing, it’s important to safeguard yourself as well as your reader community.

Today’s article is all about that, and is a follow-on to my community video, which you can find here:

I’m a middle-aged, white, straight British man who writes fun science fiction. In ten years of publishing online, I’ve had perhaps half a dozen run-ins with trolls.1 If you’re from a different demographic, or if you write about something like science2 or politics, you can unfortunately expect to encounter exponentially more bad actors.

If someone disagrees with me and engages in a good faith discussion, that’s fine. It’s a situation where all parties can come out of it having learned something, and there can be progress. I wrote about handling criticism as a writer a while back:

What I’m concerned with here is more specifically this sort of thing:

Sea-lioning, whereby a commenter attempts to bludgeon you with reasonable-sounding but endless arguments. They continually ask for more evidence, and warp the scientific method to their own ends.3

Outright, undisguised abuse and discrimination.

Spam, scams and porn.

Weird automated responses that make no sense, but which are presumably heading towards a scam of some sort. Like the bizarre Emma Horsedick incident of Easter 2025. Generative AI is the best thing that’s ever happened for scammers, so expect more of this.

Substack’s approach to moderation

Before I get into the specifics of how to use the available tools, I do think it’s useful to explore how product design , and an organisation’s attitude to moderation and community interaction, directly affects our responsibilities as writers and publishers.

Unless you’re building your own entire system, you’ll likely be reliant on external services, and tech companies have a habit of skewing this way and that when it comes to moderation and safeguarding, based not on a clear foundation of ethics but on their current reading of the political and cultural headwinds. I currently use Substack to publish this newsletter. Regardless of the particular toolset you’re using, it’s important to understand the organisation and the people behind the tools.

It doesn’t matter so much where you come down personally on freedom of expression, moderation and censorship. If you’re trying to build a readership, or a business, it’s very difficult to work with companies that continually flip-flop. Hence you have creators who built careers on Twitter, or Instagram, only for the shifting sands of algorithms and moderation to collapse their foundations.

A fundamental difference with newsletter platforms is that each publication exists as an island. I use Substack, but if I didn’t actively write about using it then most of my readers wouldn’t know or care. The tools being used to produce a newsletter that lands in your inbox are invisible and usually irrelevant. That’s very different to running, say, a Facebook group or a high profile Instagram account, where there’s no way to encounter those without Meta being all over the experience.

Substack’s hands-off approach

Practically, this means that we as writers have more freedom to write what we want. It also means that deeply unpleasant people who we might fundamentally disagree with are also free to write what they want.4

Substack received a lot of bad press a couple of years ago for its hands-off approach to moderation, at the height of the US culture wars. Some high profile writers (rather performatively, I thought) moved over to Ghost back in 2023 as a result (I’m sure the conveniently much smaller fees had nothing to do with it).5

My position is that anywhere we go on the internet will include deeply nasty people. That’s unfortunately not an internet thing, but is the reality of the world. If I go to a local pub, someone in there is likely to hold extreme right wing political views that I find abhorrent. I live in Norwich, and there will be people living in my city who are awful. Yes, Substack might make some money from awful people writing awful things. So does the pub. Even the extremists pay their council tax to the city and use the local supermarket. But I don’t think abandoning spaces as soon as someone unpleasant shows up is a sensible response: the inevitable end result will be that we have nowhere left to go.6

So, I stay. And I try to shift the balance of the world back towards something better. I write more.

What this means for those of us publishing a newsletter is that the weight of moderating our communities is also shifted back towards us. Which is a drag, but a bit of shared, grown-up responsibility is probably a good thing. Fortunately, there are increasingly decent tools for handling your publication’s community. You don’t have to put up with trolls, and you have the power to deal with them.

On the plus side, Substack’s stance has always been fairly clear, like it or not, and they’ve stuck to their principles. That has made for a far more stable base upon which to build.

Decide what you stand for

I tend to follow Wheaton’s Law, as defined by actor-philosopher Wil Wheaton back in the early mists of internet time. It’s really quite simple:

You need to decide where your red lines are, and what you are willing to tolerate. You have your own safety to consider, and that of your readers. If you have community features turned on, you need to look after them.

For a decade-or-so, outside of our personal websites, we didn’t have much control over followers’ online experience, because we’d outsourced moral responsibility the likes of Meta and Twitter. Their priority was advertisers, rather than users or society, so in retrospect it was a very silly idea to think that they cared about the likes of me and you.

There’s been a real shift with newer platforms like Substack and Bluesky, where they’ve built tools to make it easier for us to shape our individual experiences.

So let’s get into the tools. If you’re on Substack, there’s a lot you can do to shape your publication’s community experience:

1 Community moderation settings

If you publish on Substack, a big decision is whether to enable the community features in the first place. You can find the Community area in your settings:

If you’d rather not have to think about comments, you can simply turn this off. I like to enable this because I get a lot of joy from interacting with readers, but if you write in an especially sensitive area you might want to pause and consider.

Also in that section you’ll find these options:

That first one, ‘Enable reporting’, is worth exploring. Reporting on other platforms normally means reporting to the vague, hand-wavey central moderation/safety team at the organisation running the platform. That’s not the case here. If a user reports a comment they’ve seen on your publication, that report comes to you, as the writer and publisher.7

You can then view reported content by clicking the ‘Moderate’ button. That takes you here:

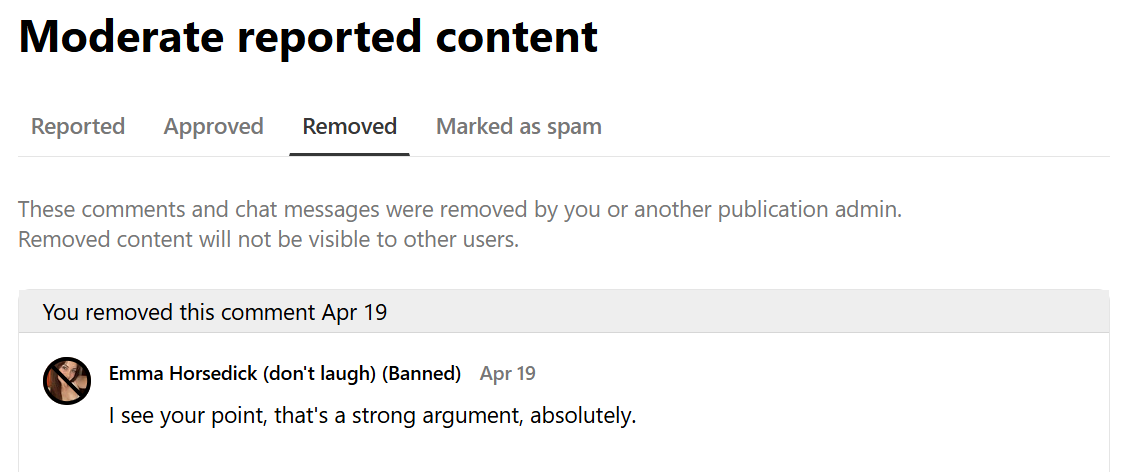

You can view reported comments, and check on what you’ve previously approved or removed. In the ‘Marked as spam’ section you’ll find anything that Substack has bulk removed, having identified it as broad spam across the network. The infamous ‘Emma Horsedick’ incident during Easter 2025, for example:

‘Manage user bans’ goes a step further, and is where you can ban specific users from commenting or subscribing to your work. This can be done permanently or for a limited time, which might be useful if you want to use it as a warning system, or to give somewhere a second chance:

Another option to manage your comments is simply to paywall them. If you have paid subscriptions turned on, you can limit commenting to your paying subscribers. It functions as a nice perk, of course, but it also logically follows that your average troll will happily make the world a worse place when the only cost is their time (they’ve got nothing better to do with their lives, presumably), but they’re less likely to actually pay for the privilege to harass others.

You can set this on a per-post basis, so it might be something to consider if you’re writing anything especially sensitive or controversial.

2 How to moderate comments and users

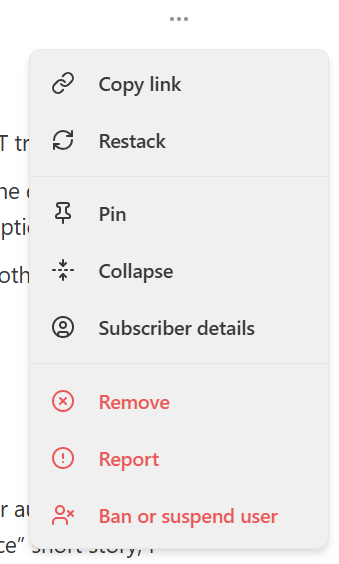

I don’t tend to go into the moderation and user ban settings. I’m far more likely to moderate comments within the comments thread itself. To the right of any comment on your newsletter you’ll see a 3-dot menu, which opens up to this:

At the bottom you have three options:

‘Remove’ simply removes the comment, but takes no other action.

‘Report’ notifies the publication’s owner (if you reported a comment on Write More, I’d get the notification), or you can switch to reporting spam or a direct violation of their content policy to Substack directly.

‘Ban or suspend user’ is how you can prevent that user from posting comments for a specific time period. You can also optionally remove all of their comments across all of your posts — useful if it’s a spambot.

You’ll find similar controls in the Chat area of your publication, if that’s something you use.

3 Controlling your Notes experience

Your publication is 100% your domain and you set the rules. If you venture onto Substack Notes, that’s no longer the case. While your interactions will be mostly with your readers and people that you read, it’s much more of a public space than the comments areas on your own posts.

There are effective ways to curate that experience. On any note, you’ll find this menu:

‘Muting’ a user means you won’t see any of their notes, but they can still see yours and read your newsletter. ‘Blocking’ means you won’t see their stuff and they also won’t be able to see yours.

A rather less extreme approach is to simply ‘Hide note’. This hides that specific note and gives you a further choice to see fewer notes like it. It’s a way to tune the Notes algorithm without getting out the banhammer.

I strongly encourage all of you to use these controls freely and without hesitation. Curate your online experience, make it what you want, because life’s too short to put up with idiots. It’s encouraging to see Bluesky also providing users with decent controls that are very similar, in terms of hiding/muting/blocking.

Perhaps we’re entering a new phase of the social internet where we’re treated more like adults, capable of making our own decisions. It seems like a healthier direction than relinquishing all responsibility to unreliable corporations, at least.

There we have it: a quick run-down on the moderation tools available within Substack. Regardless of your chosen platform, it’s worth familiarising yourself with the toolset before you need to use it. You don’t want to be frantically reading the documentation while everything is on fire.

More useful guides!

I write serial fiction in the sci-fi and fantasy genres. Tales from the Triverse is my current project, which I’ve been serialising for over three years. Being someone who likes to poke at tech and figure out how things work, I also write guides for other writers who are interested in trying a similar project.

The best place to get started is here, where you’ll find a list of the most useful resources:

That’s it for today. I’ll leave you with The Ballad of Emma Horsedick, which seems appropriate given what we’ve been talking about:

I had a less pleasant time back in the early 2000s when I was very active on YouTube: in my experience, readers tend to be more considered and eloquent than viewers.

Science shouldn’t be a controversial topic, yet here we are in 2025.

Big thanks to

for introducing me to this term. We’ve all seen it take place, or been on the wrong end of it, but it’s always useful to know your enemy’s name.I’m not a free speech hawk. As a British person, I tend to find the US-focused discussion around freedom of speech over-simplified and unhelpfully ideological. Those who shout the loudest about freedom of speech also tend to believe in it the least, and it ends up being a political cudgel rather than a nuanced debate.

Oddly, many of those same people were happy to continue using social media platforms riddled with similar or far worse content. 🤔

Side note: Substack’s designers have talked about the problem of toxic online discourse being more about algorithmic pushing of bad content than it is of moderation. It’s still to be proven, but I can see where they’re coming from. Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook: their systems deliberately surface the worst of humanity, because it encourages scrolling and ad revenue, which then leads to a disingenuous moderation/censorship ‘debate’. We’ll always have an impossible moderation situation if an algo is continually surfacing awful content. Going back to the unpleasant extremist in the pub: being in the same pub as someone like that is one thing, but the barman handing them a megaphone and regular weekly slot on stage is quite another. Substack’s recommendations work differently, and I’m only going to see something I find distasteful if I actively go hunting for it. I’ve yet to decide whether this is an example of me sticking my head in the sand, or simply the way healthy societies function.

It’s worth noting that if you do for some reason go hunting for objectionable content, and then report a comment you’ve found on a dodgy publication’s post…that report will go to the presumably dodgy person behind the dodgy publication. Something to bear in mind.

Great overview, this - I have a few people who might need it, so I'll point them your way...

Yes, understanding sea-lioning is SO important with this working-online lark. Once you understand it and can react to it, it saves so much time.

The same is true with understanding burden of proof: if someone leaps in with some cockadoodledoo theory that flies in the face of 99% of the evidence, it's NOT up to us to disprove it by watching their 3-hour YouTube video etc - it's up to THEM to prove it, clearly and succinctly, by successfully arguing away that 99%. Otherwise they have no credibility and don't deserve to be treated seriously. This is another colossal time-saver.

Nice post, great value as always 🙂 I totally missed Emma Horsedick's comments on my Substack because a) Easter, and so b) I wasn't really online - I logged back in to see the email notifications, but by then the account had been scorched-Earthed 🙂

I dig your point on Substack being a safe space for all creators. I really wrestled with this then came to the same conclusion you did - they're everywhere. I took it a step forward (in the vein of your "write more") which is that cutting off communication is where the bad stuff happens; if someone's a Nazi but we still have open comms, there's an opportunity for reform. Where much active harm was caused by Meta and the like is when private groups allowed this shit to flourish like fungus in the dark; suddenly incels didn't feel alone and were empowered by their other incel friends. Being connected in an online, open community (even with division) is better than the alternative.

Speaking of scorched Earth, I have sunset my Meta accounts (don't even use WhatsApp). There are good and viable alternatives (BlueSky, Substack/Notes, TikTok, Snap, Signal, the list goes on) with thriving communities.