Today’s post is a bit of a PSA. And perhaps wishful thinking on my part.

The TL;DR is: it’s really frustrating when strangers send me a direct message asking for me to subscribe to them, in exchange for them subscribing to me. I’m sure you’re not one of those people, but we’ve all met them, right?

Here’s the long version:

A sudden influx of people

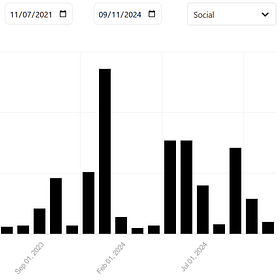

The newer online platforms for discourse and publishing have been having a bit of a moment. I saw an unprecedented spike in traffic to my publication in October and November, primarily to my ‘What is Substack?’ post. Without any hard data, my hunch is that this was driven by the US election and a general realignment of where people want to hang out online.

A lot of people were searching for ‘What is Substack?’ and landing on my little video tutorial.1 It correlates so closely to the US election, I can’t think what else might have caused it. Here’s that post, for reference:

People were curious about alternative and newer spaces. Bluesky has also enjoyed a mammoth growth spurt.

Regardless of the reason, one thing is certainly true: there’s been a big migration of people from A to B. Migration of humans is inevitable and a good thing, but it inevitably brings challenges, especially in the way different cultures clash together.

In the context of Substack, this means more writers and readers showing up, which is wonderful. It also means more scammers and bots, which is less wonderful. And in-between you get a cohort of people who are slightly lost and confused, who perhaps didn’t really want to move, but had no other choice.

Cultural quirks from older platforms are imported, often with the misguided expectation that they’ll just work straight out of the box. Just as established newsletter scribes can learn techniques from newly arrived writers, it’s also incumbent upon the newcomers to understand the spaces into which they are exploring.

Follow me, follow you

If you spend any time on Substack Notes, you’ll have seen it:

Some of these have hundreds of responses. They often seem to come in waves.2

It’s the kind of technique that used to work really well on Twitter. That was all about the size and scale of your network. It didn’t matter too much who people were, as long as you were connected to them, and therefore benefiting from the network magnification effects.

Following was the name of the game. But the game has changed.

Subscription-based platforms are not solely about scale. Going wide is less important than going deep. The quality of subscribers is more important than the raw number: that’s why I’m so grateful to have you lot on the other end of this.

Before I go further down that line of thought, a quick aside:

Guard your email address

It’s important to remember that the newsletter and subscription space works slightly differently to those older platforms.

Following someone on Bluesky doesn’t reveal much of value to that person, other than your Bluesky profile. Same with Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and so on. Obviously you can provide additional details on your profile, and people can follow breadcrumbs fairly easily, but the point is that if you want to stop using Twitter, for whatever reason, you can just stop using Twitter. All those follows just kinda stop.

Subscribing to a newsletter provides the creator with your email address, which is a much more valuable asset — for both you and them.

It’s not like you can easily stop using your email address. You’ve probably had it for decades. You can unsubscribe, of course, and any decent creator or company will respect that. For example, if you unsubscribe from my newsletter, you’ll never hear from me again unless you choose to come back.

But if you subscribe to A Dodgy Person, that means they’ve got your email address. If they don’t respect privacy rules, they can continue hassling you. It’s the online equivalent of they know where you live.

This is why the subscribe-for-subscribe thing is bad news. Sure, in a lot of cases it’ll be a misguided person who thinks it’s a good tactic (more on that below). But it can also be used by bad actors to hoover up a load of email addresses. These will then be downloaded off Substack or Ghost or Beehiiv or Mailchimp and fed into bot networks and other data farms, and the spammers have got you.

Obviously, what I do here is reliant on people trusting me with their email address. That’s why this subject is so important: there’s an inherent trust exercise at work when we subscribe to someone or a company. The subscribe-for-subscribe crowd risk upending that trust dynamic, and opening the door to Dodgy People.

It’s also a waste of time:

Big vanity metrics are pointless

The ‘social’ era of the internet led us collectively down a dead end path. It was all about follows and building up those numbers. You needed thousands of Twitter followers to have any kind of influence. You needed tens of thousands of Instagram followers. YouTubers need hundreds of thousands or millions of subscribers.

It’s silly, and unsustainable.

Especially when platforms change or go pop. All those years building up Twitter followings, and now people and organisations are choosing to start over on completely new platforms. Rinse and repeat every internet cycle. So much time and effort dedicated to growing a number that ultimately meant nothing. You can’t take your Twitter followers with you.

Somewhere along the way the focus became about the number itself, rather than why it was useful to have ‘followers’ in the first place. With the slow-then-fast implosion of many of these spaces, it’s become abruptly apparent how meaningless these metrics were.

If you’re still using Instagram, is anyone even seeing your stuff?

wrote about this exact thing when she popped up on Substack recently:If someone with her reach was feeling entirely unseen, what hope for the rest of us?

The solution to these issues is not to move to a copycat service and start all over again, chasing the big follower counts. It doesn’t matter where you’re getting your drugs from; the point is that you’re still hooked.

To be fair, there have been periods where large followings have manifested in useful ways. Furthering an activist movement. Promoting a new and unusual product. Building a career. Showcasing your work. A lot of that wouldn’t have happened without the scale afforded by the big social platforms, but it’s been diminishing returns for a while now.

The problem is the mentality shift. When the motivation becomes get a bigger number, that’s when the platform has got you. You’re no longer using it as a tool: the platform owner is using you as a tool.

A metric is supposed to be used as an indicator of travel, but probably shouldn’t be the destination.

Meaningful interactions

Which brings me back to newsletters, and subscriptions more generally. This applies to spaces like Substack, Patreon, Ghost and so on. The critical thing is that these are all creator-owned to some degree: sure, the companies powering the tech are often private, but we control our interactions. We own our material and our subscriber lists, and can go elsewhere if needed. We’re not trapped.

The relationship with the audience is different. If you’re writing a newsletter, running a Kickstarter project or maintaining a Patreon page, the numbers are flipped upside-down. It’s not about big numbers anymore. Those top-of-funnel, only vaguely interested, fly-by people are not useful. What you want are deeper, more meaningful connections.

Smaller overall numbers, but more enthusiastic, more direct:

Subscribing to a newsletter, or supporting a Kickstarter, or joining someone’s Patreon, requires a very different attitude and investment to clicking ‘follow’ on Twitter or Bluesky. A ‘follow’ on Twitter was a throwaway thing; an easy decision, low commitment and low effort.

That doesn’t work with subscription-based systems.

If the connection between creator and audience is not genuine, then it’s never going to develop into something useful — and that applies whether you’re seeking a free audience or paying subscribers. You want people to pay attention and engage with the work, not just glance at it as they scroll idly past.

Having lots of subscribers is lovely, of course. More the merrier. Scale is not nothing. But the quality of subscribers has to come first. And then creators are dealing in a much more predictable economy, which can be built upon.

A subscription has to be a conscious decision

Which brings me back round to those silly subscribe-for-subscribe viral Notes.

Gaming the system and pursuing growth hack tactics can feel like a win in the short term. Look at those follow and subscriber numbers going up! Ding ding ding.

It means nothing. If someone subscribes to you for no reason other than you subscribed to them, it means they’re not interested in you or your work. They’re only interested in their own growth. Quid pro quo doesn’t get you far here.3

Those people will never read your stuff. Most of them will hit unsubscribe as soon as you actually send anything out. Even worse, they might consign your work to the spam filter, training email clients to consider your material of lesser value.

Another way to think about it is in terms of gifts. A birthday or Christmas gift lacks meaning if you’re only giving it because the person had already given you a present. It shouldn’t be a reciprocal thing. A gift is something you choose to give because that person is important to you; whether they give you a gift in return or not should be irrelevant.

A subscription is the same. It’s a way of saying to a writer, or a musician, or an illustrator, or a filmmaker: I like specifically what you are doing as a human. Keep doing it.

Better ways to grow

Spoiler: growing an audience in a meaningful way tends to be a long-term thing. It’s going to take a very long time. It requires patience.

Some very basic starter tips:

Don’t message people asking for follows/subscribes. It is ultimate cringe.

Do message people if you genuinely find their work interesting and want to talk to them about it. People tend to like that.

Don’t try bait-and-switch tactics. Waste of everyone’s time, including yours.

Do be up front and honest about what you’re offering. You want people who are properly interested in your work. Be proud of the work.

If you’re very niche, lean into that, don’t try to disguise it.

Take part in conversations when you have something to contribute.

You don’t always have to have an opinion. If you don’t have anything new to contribute, it’s probably best to stay quiet.

Don’t shoehorn in a link to your work every time you join a conversation. People will recoil.

Be generous with your knowledge and expertise.

Seek collaborations with others in your field.

Be consistent in your publishing schedule.

Aim for the highest possible quality at all times. Note: what this means will depend on the specifics of what you’re doing.

Get to know a community before diving in. If you’ve just come from Twitter, don’t assume that other spaces are like Twitter, etc

Aim to be an interesting, pleasant person. Seriously, it works!

If you want more detail about newsletters specifically, I’ve written two posts about growing a newsletter in a healthy, legitimate way:

How to (very, very slowly) cultivate a fiction newsletter: part 1

Writing fiction is hard. Finding readers is even harder. Achieving success, regardless of how you personally measure it, is near impossible.

How to (slowly) cultivate a fiction newsletter: part 2

There’s a reason I’ve used the word ‘cultivate’ in the title of these articles, rather than ‘grow’, or any of the other icky LinkedIn-style corporate terms.

OK, that’s the end of the PSA. I hope it didn’t come across as a rant.

Thanks for reading.

Meanwhile.

Stuff I’ve been enjoying:

I’m experimenting with a monthly column called Footnotes. It’s intended as a fun bonus or paid subscribers, providing some extra behind-the-scenes insights and info on what’s coming up.

Also for paid subscribers, I’ve updated the Tales from the Triverse ebook to include everything up to the latest storyline. It’s the best way to catch up on or re-read the series.

I always read Platformer with a carefully raised eyebrow. Its performative departure from Substack always seemed a little odd,4 but it still has its finger on the social media pulse. AI, I’m not so convinced. ‘The phony comforts of AI skepticism’ feels more like a hit piece than useful journalism, designed to generate controversy rather than insight. Doesn’t entirely fit with their ‘No hot takes, ever’ mantra.

- responded to Platformer with this. Popcorn time. My main takeaway here is how tribal AI has already become. That birfurcation is only going to intensify, for both creators and audiences. I suspect it’s all going to get quite awkward.

I’m still playing Balatro. Help.

I read the first issue of Jamie McKelvie’s One for Sorrow. It’s the first thing I’ve read of his that wasn’t written by Kieron Gillen. I’m pleased to say it is very, very good. People should not be allowed to be this skilled at multiple things.

Started reading Abaddon’s Gate, the third novel in the Expanse series. I loved the TV show and the books are equally excellent. Comfort reading, but decent nonetheless.

We made a cake for our son’s birthday. Believe it:

See you all later in the week for the next Tales from the Triverse chapter.

I should note that this was never the plan. The ‘What is Substack?’ video I made back in September 2023 was because I wanted to try making some video tutorials for other writers, and that seemed like a logical place to start. That it turned out to be catnip for search engines was a fluke. It’s great to bring in new readers, of course, but I can’t help but think a lot of them must get very confused when they receive a new chapter of Tales from the Triverse.

This makes me think that at least some of them are bots, or automated in some way. Or perhaps they’re all copying and pasting from the same awful ‘growth hack guru’.

There are exceptions, of course: I’ve sometimes subscribed to people after they’ve subscribed to me, but that’s when I’ve looked into their work and found it interesting. Their initial subscribe may have alerted me to their existence, but subscribing back wasn’t me returning the favour, but making a conscious choice.

Taking a stand against some of the offensive material on Substack is completely fine, and I respect that, but there’s no online space which doesn’t feature offensive people. Just like there’s no city, no street, no pub that doesn’t include offensive people. I’m not convinced that ceding spaces is the best approach, because the logical end point of that is that we lose everywhere, and the only people left are the Nazis.

Usually the quid pro quo is derided as inappropriate, because if there's no common ground between the two writers it's meaningless. So your point about people being more circumspect about how often and with whom they share their address is valuable, and a stronger argument not to do it.

As soon as a measurable is set, the measurement becomes the goal, which renders the measurement pointless. This is true everywhere, not confirmed to social media. Businesses can meet all their KPIs and still be providing crap service or defective products. The measurement ends up negating the thing being measured.

In the online world, mere reach has become useless, I think just white noise.

As for sub for sub, it's naive and foolish. It shows a misunderstanding of the environment.

In the old days, having large numbers of followers or likers on platforms like FB and Twitter actually did something. People regarded it as social proof and assuming there was more value in what you had to say. But, as you so rightly point out, subscription is a bigger commitment here than just following someone. And just having the numbers no longer helps those numbers to grow, anyway.

To your excellent points, I will also that Substack is now starting to accumulate a supply of scammers and/or bots. I noticed them because sometimes they look like readers--and we all want to find readers. But every time I try to pursue an actual reader, the "people" I find just want to have small talk with me that usually culminates in a request for personal information, an attempt to pull me to another platform, or something like that.

The moral of the story is to vet people, even those you follow, but especially those you subscribe to. Someone who shows an interest in your may also be interesting to you, but that's not a given. And, even though I hate to say it, someone with no information in the profile is not a good bet. This person could be someone who just wants to find new reading material, but my experience suggests that they are mostly not what they appear to be. They may randomly follow and free subscribe to make themselves look real, but you can usually tell if you examine what they're doing closely.