How Substack's recommendations system can be used by fiction writers

What it is, how it works, why it's (still) a game changer

Being a writer of fiction is hard. Actually writing the text in the first place is astonishingly difficult, both in terms of finishing it and making it any good. But then comes the fiendishly difficult bit: the part which is akin to the alchemists of old, trying to transform lead into gold.

I’m talking about finding readers, of course.

Snow leopards are rare and difficult to find. Here’s a photo of a snow leopard:

If you search on Unsplash or Google, you’ll find loads of photos of snow leopards.

Search for ‘fiction reader’, though, and you won’t find anything. There are no photos of fiction readers, which tells you just how rare they really are. That’s why when you do find one, you have to cherish them, make them feel welcome and tell them really good stories.

If you’re a writer on Substack, this process is made slightly easier by the Recommendations feature, which is what I’m going to dive into today.

What is Substack’s Recommendations feature?

At first glance, the Recommendations feature seems very obvious and rather basic. There’s nothing evidently revolutionary about it. A writer of a Substack-powered publication can select another Substack publication and recommend it.

Big whoop.1 Isn’t that something we could do anyway, without needing a ‘feature’ and interface?

Well, sure, and writers were indeed doing this across newsletters before April 2022, when the Recommendations feature appeared. As a one-off thing, mentioning someone else’s work could still be highly effective: if a high profile writer linked to your newsletter, it could bring in a lot of new readers.

But it was fleeting. What Substack has done is baked the concept into the platform down to its foundations.

Let’s do an example

I recommend

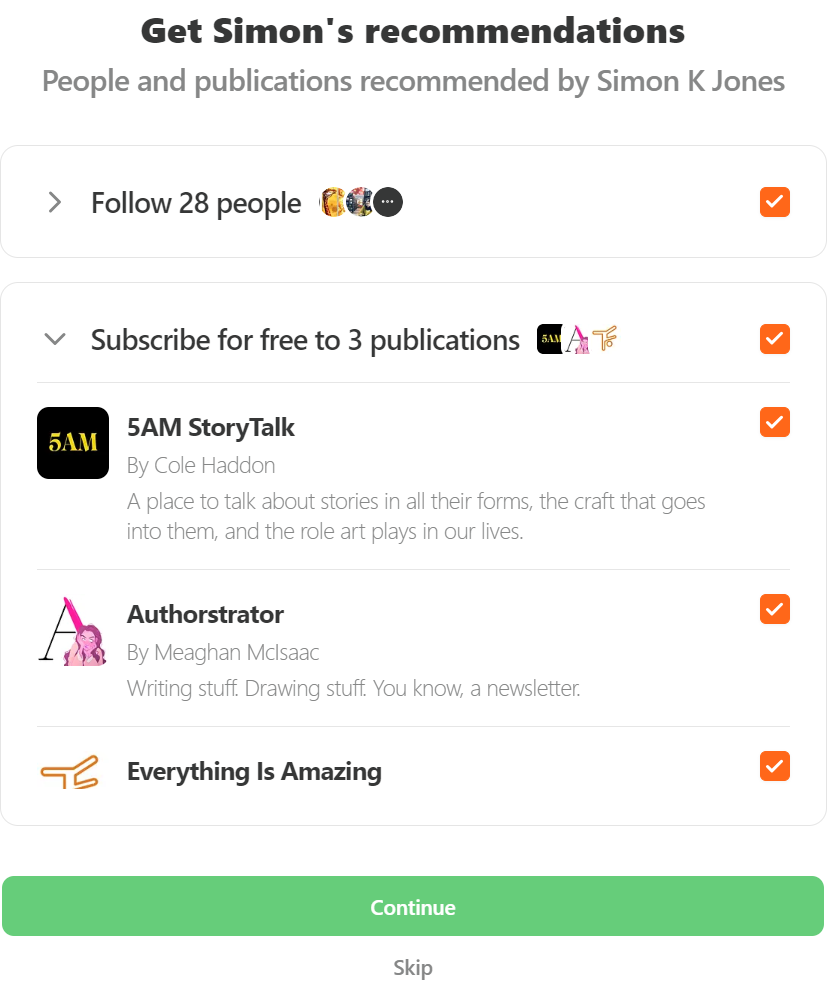

’s (you should follow him, he’s nice) (you should read it, it’s good). What that actually means is this:When someone signs up to my newsletter, they’ll be shown a selection of the newsletters I recommend. This is automatic. They can skip, subscribe to them all, or hand-pick the ones that look interesting. It looks like this:

Every-so-often, an email is sent out to subscribers, highlighting some of the newsletters I recommend. It’s worth noting that you can turn this off, if you don’t like the idea of Substack sending emails on your behalf. Here’s an example:

Building recommendations into the core user journey, during initial sign-up as well as the casual reading experience, completely changes the nature of how recommendations work.

I’ve sent 120 subscriptions to Mike’s newsletter. It’s a tiny drop of his (well-deserved) readership, but it’s not nothing. You can bet a lot of other people are recommending

— some of them will have small followings, some very large, but they all add up to something significant.For some extra context, here’s what the Recommendations feature has done for me:

Why it is so effective

The Recommendations feature works for several reasons:

Once a writer has recommended someone, they don’t have to think about it again. The system will continue recommending that newsletter automatically (unless the writer changes their mind and removes the recommendation). For busy writers, this is essential.

It builds it into the onboarding process. At the point a new reader is subscribing, when they’re exactly in the zone of “this writer seems interesting!”, that’s when the recommendations pop up.

When you recommend someone’s publication, they receive a notification. This might be enough for them to check you out, which could be the beginning of a wonderful conversation.

This isn’t the same as a simple ‘friends of friends’, or some algorithmic ‘you might also like…’ suggestion. Back when I used Twitter, if I followed someone I’d get a bunch of suggestions, but those were not coming from the person I just followed. They were driven by algorithms and the priorities of the Twitter platform and company and its customers (by which I mean advertisers). That’s not what a Recommendation is, in this context. Which leads me to:

Recommendations are fully curated. If I recommend some newsletters, it’s because I, personally, think they’re worth recommending. There’s no algorithm. There’s no other agenda. It’s just me thinking “hey, this is cool, my readers might like it, too.” And if someone has chosen to subscribe to me, that means there’s a good chance they’ll like the recommendation, because we already have that link and some kind of shared interest.

That hand-curated aspect is the key, and must not be overlooked. It’s what sets the world of newsletters apart from social media. If someone doesn’t like my newsletter, they won’t see my recommendations either. But if we’re aligned in our interests, there’s a good chance that there’s a mutually-agreed rabbit hole to jump down.

1,000 of my almost-5,000 subscribers have come via the Recommendations feature.

That is HUGE. I remember, not that long ago, when I hit 1,000 subscribers total, and thought that was an insane number. It’s not something I’d ever anticipated reaching.

Note the subtle-but-noticeable uptick in subscriber growth almost as soon as Recommendations launched in April 2022:

It had taken me about nine months to get to 500 subscribers. It took me six months to get to 1,000. A big part of that acceleration is down to Recommendations.

It’s old-fashioned word-of-mouth, then?

An old-fashioned concept matched to 21st century technology, sure.

Just like newsletters themselves. People have been sending newsletters to each other since the invention of the printing press. They pre-date the internet and email by centuries. Email made it easier, and the likes of Substack, Ghost, Beehiiv and the others have made it easier again.

Networking is not something that many fiction writers enjoy. It’s awkward and it distracts from the main task. Recommendations semi-automate every part of the process, except the act of choosing the recommendation in the first place.

Remember, it’s not just one person recommending another. That’s how it starts, but it’s only the beginning of an ever-expanding spider’s web. I recommend Mike’s work, and one of my subscribers decides to subscribe to

. That reader than finds some other newsletters that Mike is recommending. Perhaps the reader is also a writer, and decides to recommend both me and Mike — or someone else entirely. The network expands organically, based on real human connections and interests, rather than machine orchestration.A common concern around here is that ‘the only people on Substack are writers’. I highly doubt this is true, but writers are certainly over-represented compared to other platforms.

But you know what that means? An even stronger Recommendations network. If your work is reaching other writers, then they will have their own publications, where you might be recommended. And the thing is, they will definitely have some subscribers who are not writers.

If you write science fiction, or literary fiction, or romance, then you want to get in with those crowds, and those writer communities. Recommend each other, if you think the work is good, because that’s how readers will find new material.

I mean, imagine going into a bookshop and your favourite writers are all there, and they’re enthusiastically recommending their favourite writers. Sounds pretty useful.

Virality with value

‘Going viral’ was something that became a sought-after phenomenon a decade+ ago. It was the Big Break! The way to become famous, or successful, or both. To be noticed. It was a shortcut, and extremely unlikely to actually happen.

Virality in the social media era — by which I mean from around 2005 to 2020 — was a magic trick; a random combination of unrepeatable factors. It was a shifting target, as the corporations changed the rules. There was nothing for a creator to build upon.

Virality in the post-social era, which really needs a proper name (the curated era?), is rooted in choice and human connection. The machines are there to make what we’re doing more efficient, not to make the decisions for us. ‘Going viral’ on Substack has a very different meaning and consequence. It’s not about a flash in the pan explosion of attention, but a slow spreading of awareness and growth. The Recommendations network is the engine behind that slow-virality.

How do I get recommendations on Substack, then?

The short answer is very simple: do good work.

That’s always the first steps. Nobody is going to recommend you if there is nothing to recommend. Remember, this isn’t a dumb algorithmic machine to be gamed and tricked; it is humans you have to convince.

Of course, you still need to actually be noticed. Some ways to do that:

Post on Substack Notes. This isn’t a magic bullet, nor handful of magic beans, but it is another very powerful tool in Substack’s arsenal. Post authentically and genuinely, and share Notes that are relevant to what your newsletter is about.

Read other people’s newsletters, and take part in discussions. Leave interesting comments, and people will be curious and check out who you are and what you do.

Recommend your favourite newsletters. When you do so, you’re helping your readers and helping that writer. The other writer will receive a notification, too, and who knows what that might lead to?

Seek out writers who operate in a similar area to you. You likely have audiences that share interests as well.

Start conversations with other writers. Genuine ones, not fishing trips where you’re hunting for recommendations. Don’t be that guy. But get in touch with writers you love, because you never know what might come from it. Possibly, down the line, a recommendation.

There is no shortcutting any of this. It will take time. Remember, we’re talking slow virality here. But you love writing anyway, right, so that should be no problem.

Perhaps more important is what not to do:

Don’t drop into the comments on someone else’s newsletter and promote your own work. Nobody likes that. Leave a genuinely valuable comment and people will check out your work anyway, without thinking you’re rude.

Never, ever direct message other writers and ask for a Recommendation exchange. That’s not how this works. That’s not what recommendation means. A recommendation only has worth if it is an informed decision. If writers recommend other writers based on personal requests, the whole thing falls apart and writer-reader trust evaporates. So let’s not do that, OK?

Never, ever direct message other writers and say “hey, really like your stuff, and I just recommended your newsletter. No obligation, no pressure, but if you’d like to return the favour, that’d be cool!” Remember: they already know you recommended them, because Substack told them. That was a good feeling. If you follow it up with a passive aggressive message, you’re spoiling that first impression.

Remember that the newsletter game, and especially the fiction newsletter world, is not LinkedIn.

In fact, keep the motto This is not LinkedIn at the forefront of your mind at all times. Perhaps print it out and stick it next to your monitor. Or get a tattoo. This advice applies to all aspects of life, by the way, not just Substack.

I really recommend checking out

’s article about Substack network design more broadly, which is a fantastic primer for any writer around these parts who wants to better understand the infrastructural core of the platform as well as the opportunities:Thanks for reading.

The school summer holidays have rather got in the way of more in-depth articles like this one, so I’m very pleased to be back with a proper how-to.

Putting this together was prompted by a few things:

’s article, for starters. Also the increasing number of DMs I receive from people asking for recommendation swaps — which is frustrating, but also an indicator of a deeper misunderstanding of how the feature works. Maybe this will help to point people in the right direction.It’s also me trying to figure out how and why Recommendations have been so helpful to me. I’ve never sought them, or actively employed tactics to encourage them. It’s just sort of happened, as a consequence of writing a weekly newsletter and sticking my nose into conversations when I have something useful to contribute.

And isn’t that amazing, and something worth celebrating? Significant growth based not on hacks or flukey one-offs, or contorting myself to dance to an algorithm’s ever-changing tune, but on simply doing the thing I wanted to do anyway.

I write what I love to write, talk to people I want to talk to. And Substack’s tech is there to make the most of those genuine moments of human connection. Hopefully this article will help other writers, especially those of you starting out, follow a similar path.2

Meanwhile in completely unrelated rando things:

Tom Francis’ Tactical Breach Wizards is what I’ve been playing, and it is very good. The writing is also excellent, and far more clever than I’d initially realised. I love it when a writer turns out to be even cleverer than you’d thought.

Beat my personal best time at the local 5k parkrun on Saturday. That felt good. Though it feels less good today, as my body complains.

A huge hello to all of you new subscribers. Lovely to have you here! If you’re a paid subscriber, do check your welcome email for links to the Triverse ebook and the buttons for booking a 30-minute chat.

Still watching Naruto Shippuden with the boy. It continues to be an astonishing storytelling achievement. So pleased to have had an excuse to discover and watch it in my mid-40s.

To sign off, here’s a photo I took on my morning walk last week. Might be one of the last mornings like this, before the autumn and the rain sets in:

Yes, that’s a Monkey Island 2 reference.

Or, ideally, an even better one.

Thanks for the shoutout Simon! I think I’ll link to this piece as a resource for a more detailed breakdown of Recommendations in the network post

“A common concern around here is that ‘the only people on Substack are writers’. I highly doubt this is true, but writers are certainly over-represented compared to other platforms.”

I have thought this also. However, even if it were true, most (if not all) writers read more than they write anyway. So in theory this should be a good thing, right?