Developing your style can't be rushed

On going back to the beginning

The latest episode of

and Dave Kellett’s Comic Lab podcast is all about developing your own art style, which got me thinking:Their main point is that this not something that can be rushed. You can’t magically develop a ‘style’ overnight. Copying a pre-existing style might be possible, if you’re technically accomplished, but it still won’t be yours.

I’ve produced a huge amount of written material over my life, and especially in the last decade since I started serialising stories every week. Hundreds of thousands of words of fiction and non-fiction, and that’s without counting copywriting in the day job. I’m confident in my writing voice.

That’s not what I’m going to focus on as an example here. Instead, I’m considering my attempts to be a better illustrator, which are in very early stages. I’m still trying to figure out my visual style, and it’s an interesting process to go through having already gone through it with my writing.

A lot of what I’ve figured out along the way I suspect applies to any creative pursuit, be it drawing, writing, composing music or anything else.

Be warned, I’ll be sharing my some of my amateur drawings as this post progresses.

Quick aside — I explored how long I’ve actually spent writing in this slightly silly article from last year:

10,000 hours

A friend recently reminded me of the ‘10,000 hours’ concept. The idea is that to become expert in any subject you need to actively do it for at least 10,000 hours.

The sheer amount that I’ve typed out resulted in my own style emerging, eventually. It’s very difficult for me to describe that style, of course, but presumably my regular readers can identify ‘a Simon K Jones story’ compared to, say, ‘a Naomi Alderman story’. I’m reasonably confident that when I write fiction or non-fiction, I’m writing in my unique voice. It shifts and changes per-project, of course. A Day of Faces is different to The Mechanical Crown and No Adults Allowed, but they are all very much me.

This wasn’t always the case. In my teens and twenties, my stories would read like I was trying to mimic other writers. I’d write robot stories in the style of Asimov. Hard sci-fi in the style of Kim Stanley Robinson. I wonder sometimes whether we all start out as writers of fanfiction, because in the very beginning all we can do is replicate what we have read, whether we mean to or not.

At some point, all the accumulated technical skill and story inspiration we’ve absorbed from other writers and the world in general combines, and filters through our particular brains to form a new style. At that point, you’ve become definitively you.

My drawing is another matter. I’m very new to illustration, other than sketching out basic comics as a kid. Listening to the Comic Lab podcast made me realise how I’m still very much at the beginning of a new journey — which is an exciting place to be, but requires starting from scratch. Once Tales from the Triverse wraps up, my next project is most likely to be comic-related, which is why I’ve been quietly trying to improve my drawing ability.

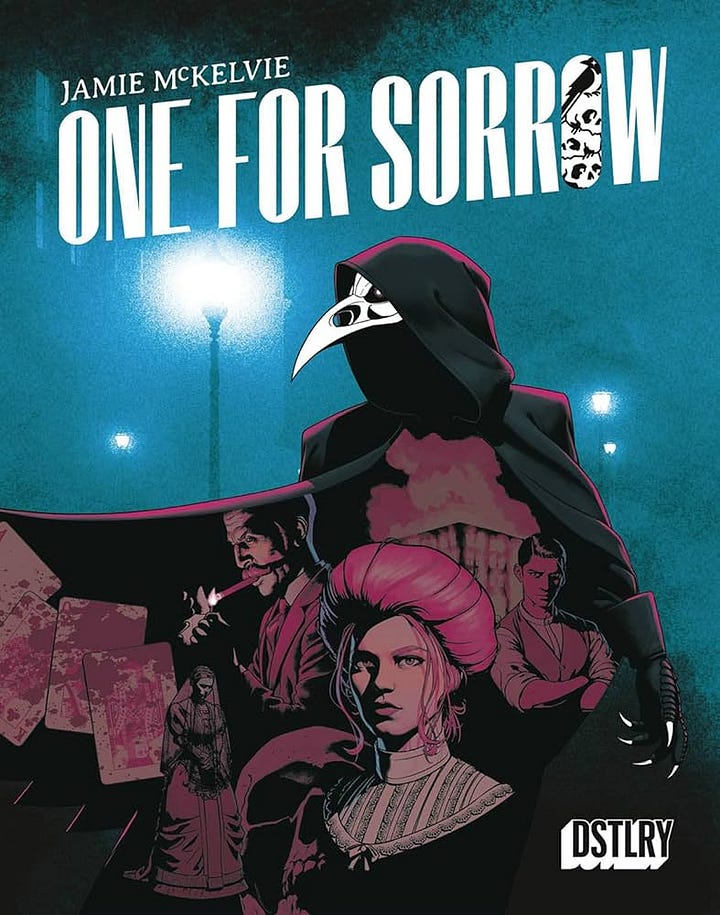

Landing on ‘a style’ for my drawing has been the challenge, partly because I didn’t really know what that even meant from a visual perspective. I know what I like, and have artists that I admire. Chris Foss, Moebius, Jamie McKelvie, Dave Gibbons, Andrew Wildman, Norm Konyu, ND Stevenson, Daniel Warren Johnson. Concept artists and comic artists feature a lot on my list. Then there’s all the classical stuff, the sort of thing you see on the wall of the National Gallery, or the experimental projects in the Tate Modern.

So many influences! But I’ve never really understood how any of that relates to what I want to do. If I read a book by an author I enjoy, I can immediately learn from what they’re doing, observing and picking apart their approach. That’s not been the case with visual art for me, and that gulf in expertise has been frustrating at times — I think perhaps I expected to be good at art because I was good at writing, which clearly makes no sense. It’s a humbling experience to go from something you’re very comfortable doing, to an entirely new and unknown skillset.

Somewhere along the way I got a bit lost. Reading something like The Wicked and the Divine, and adoring it, I wanted to be able to draw to that standard. In order to tell comic stories as compelling as Kieron Gillen, I thought I needed to be able to draw as expertly as Jamie McKelvie.1 The problem, obviously, is that nobody can draw like Jamie McKelvie except Jamie McKelvie.2

OK, I thought, so it’s not that I want to replicate McKelvie’s style, but that I want to be able to draw in realistically. For the kinds of stories I wanted to write, I needed to have realistic human faces and bodies — anatomically convincing and consistent in design. And for a long while, that became a brick wall. I’m simply nowhere near being sufficiently skilled to pull it off.3 Nowhere near. Ludicrously far away, in fact.

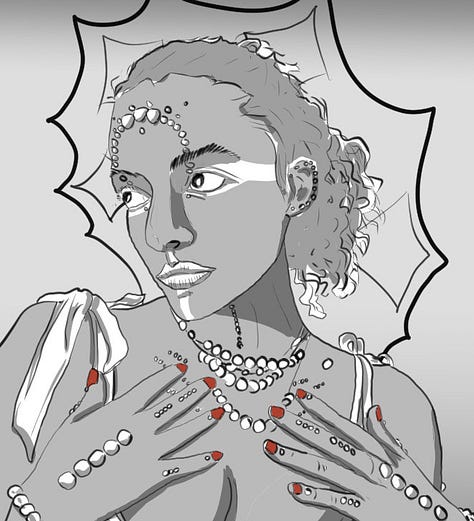

Look through my art folder and there are countless appalling attempts at drawing semi-realistic human heads from my own imagination. I then thought I’d found a way forward using photographic reference. Turns out I can copy a photo without problems, and had some fun with developing an ink style that I enjoyed, and for a time thought that was a good direction to go in:

The problem was that unless I found (or shot) precise photo reference for everything, it wouldn’t work. I wasn’t actually drawing, I was copying. As soon as I tried to draw the same person from a different angle, it fell apart.

I had a go at Mermay, after hearing about it from

. Some of my sketches were OK, but again they were all heavily based on photo reference. Even with lots of alteration, it felt like I wasn’t able to break out and do my own thing.

I think it was

who challenged me at some point to draw without using direct digital photo reference. Which was when I properly realised that I couldn’t.Everything I’d been doing was replicating someone else’s style, whether a photographer or an illustrator. I was learning some useful techniques about line art and colouring along the way, sure, but if I took the training wheels off I immediately fell over.

As Brad and Dave point out in their podcast, I was trying to skip to the end without putting in the work.

I mistakenly thought that this meant I couldn’t make comics.

The breaking down of that mental wall, perhaps inevitably, also involved Kieron Gillen:

I had been so determined to mimic the qualities of a Gillen-McKelvie comic, was aiming so absurdly high, that I’d been sabotaging my own early progress.

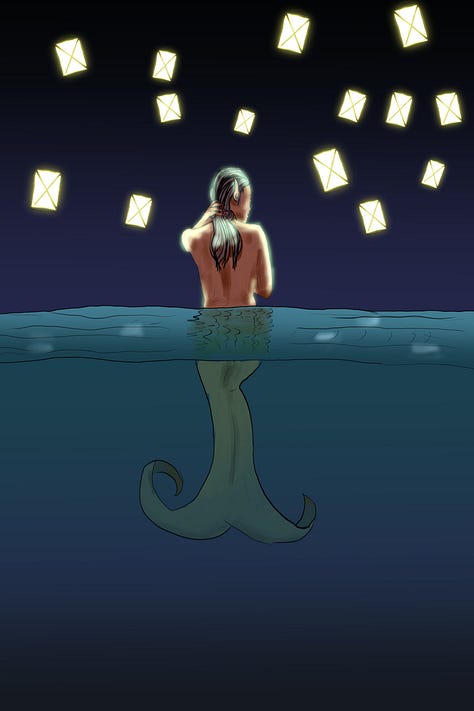

Except, secretly even to my own brain, I had been making progress towards a more distinctive and personal style. I just hadn’t recognised it. Or perhaps I’d refused to recognise it. During Mermay, I sketched this without using photo reference:

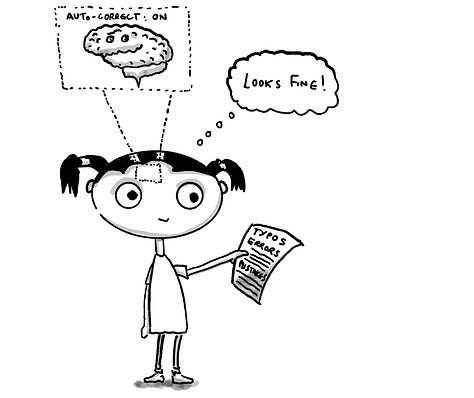

Cute! I like to call this ‘Big Head Style’. I got some positive feedback from my family, who pointed out that I should do more with Big Head characters.

But that’s not my style! I want to draw realistic and moody and dramatic stuff!

I resisted it for a long while. I think perhaps I had some deep-down prejudice against more cartoonish drawings. The idea that a cartoony style can’t be used to tell meaningful and serious stories is, of course, bobbins.

You’ve probably seen some Big Heads pop up on the newsletter over the last year-or-so.

I’m not the only person to draw characters with big heads, obviously. This isn’t an especially unique cartoon approach. But it does feel like an aesthetic that I can keep developing and make my own. Trying different shading techniques, figuring out how to use colour, working out how to incorporate dialogue balloons.

Telling stories.

It’s something I can work with, in other words. It comes from my imagination, and I don’t need to lean on photo reference.

As Gillen pointed out on Bluesky, making comics is all about getting the best from an artist’s limitations. The more I tinker with the Big Heads, the more I realise that I can create distinct characters, with personalities — which is all you need to tell a story. I just had to get over myself and embrace a ‘cuter’ visual style, rather than trying to force myself down an uncomfortable path.

The point, if there even is one in today’s newsletter, is that figuring out your style isn’t a linear process. I went through all of this with my writing, as well, I just started it decades ago, and pinned it down when I started writing and publishing serials on a consistent schedule.

Pursuing a specific style that you’ve seen elsewhere likely won’t work, because you’ll just be trying to ape your favourite artists or writers or musicians or what-have-you. You can’t force a style. It has to appear by itself, over time. It probably won’t be what you expect, and it won’t arrive when you want.

If you’re early in your writing, don’t despair if you’re struggling to find your voice. It doesn’t matter if you’re still replicating your favourite authors, and writing fanfiction is an entirely respectable way to learn the craft and figure out who you are. When we are beginners, we copy and we copy, learning piece-by-piece, until one day we find ourselves accelerating away from those early influences and finding our own path. That escape velocity is what you’re seeking. That’s the point at which you are your own artist, and it’s what distinguishes you from everyone else. In an age of infinite content, it’s a vital moment of transition.

Time is the primary lever here, as Brad and Dave pointed out in their podcast at the top. There are no magical shortcuts. You can’t get to the destination without first going on the journey.

Meanwhile.

Thanks for reading!

A key part of my writing over the last decade+ has been to share the work publicly and early. That creates momentum and a commitment that keeps me coming back to the page.

Sharing the drawings in this post is performing a similar function. It’s uncomfortable for me to put up my amateur sketches but, by declaring it as A Thing I’m Doing, I hope to compel my brain to carry on. If that sort of approach sounds useful, I have a 22-part guide all about serial fiction writing and publishing that might be useful:

How to write serial fiction index

This is a 22 chapter guide to writing serial fiction, taking you from understanding the core form of serial storytelling, through plotting and themes, character creation, plot twists and much more, all the way through to hitting the ‘publish’ button. I’ve been writing serial fiction for over a decade, so I know a thing or two about how it works.

See you on Friday for more Triverse.

Hiring an artist is an alternative approach, but my main interest for the moment is in writing and drawing a comic.

Which isn’t to say that I can write as well as Kieron Gillen. Obviously. But I can at least write to semi-decent quality. It’s not a blocker.

Not without going back to school, at least. Which isn’t impossible! But it’s not an option right now. One day, perhaps.

Life drawing classes are valuable. Regardless of how your style ends up. And going out into the world and drawing what you see. Characters need backgrounds. All learning is good, no matter the source.

Genuinely have no idea if I have a 'voice' as a writer. I remember making some flippant remark at one of my launches (urk, "one of my launches", what a d*ck) about how one of the reasons I wanted to write in different genres was so that people could pick up one of my books and not necessarily realise it was me, rather than being distinctive.

I wonder now if that's an expression of my introvert/extrovert paradox - my innate need to show off while simultaneously not have people look at me.