Author + reader = story

Don't skip the conversation

I was listening to an episode of The News Agents, with journalist

interviewing Jack Clark from AI firm Anthropic.“Today, lots of people use these systems to learn, but some of them use these systems to do junk food learning, and some use these systems to do effective learning. ‘Junk food learning’ is: upload a research paper, and say ‘tell me what this research paper is about,’ and then read the output. You haven’t actually learned anything there, you’ve just become dependent on the machine in a way that doesn’t help anyone. The way that I use these systems, and many do, is: I read a research paper, I write out what I understand that paper to mean, and then I upload that paper and my understanding of it to the system, and say ‘do I have this right? And if I don’t have it right, explain it to me.’ That’s useful learning.” Jack Clark

This is the difference between using AI as a tool and using it as a shortcut.1

Sometimes a shortcut makes sense, but take too many of them and you might miss something along the route. Going for a walk isn’t always about reaching a destination — sometimes it’s about the walk itself.

Jack Clark’s comment reminded me, somewhat tangentially, of this recent observation from

:I taught a workshop on storytelling in games many years ago (I’m not a games dev, so this was something of an accident), and subsequently turned it into an essay that you can read here:

Storytelling in games & books

I used to write about games more than I do now. Most of my time is taken up with my own fiction and writing about writing, but I think I’ve always been a frustrated game designer at heart.

One of the key points in that post is that interactivity is not unique to games, despite it often being pointed to as the defining characteristic:

It’s easy to think that interactivity is the key difference between games and literature. Video games are evidently ‘interactive’, in that the player can affect what happens to a greater or lesser degree. This is what makes them unique as a form. It’s an easy statement but in the context of stories misses the point that all forms of storytelling are interactive.

When people go to Wikipedia to read the summary of what happens in a movie, or use AI to create a quick outline of a novel or report, they’re essentially skipping the interactive part.

In the case of a movie, reading about the plot will never match the experience of that same story unfolding in front of you as intended by the filmmakers. An overview of The Great Gatsby isn’t the same thing as the sensation of reading it. Skimming a one-pager version of an 80-page scientific report does not lead to the same level of understanding. It bypasses the opportunity for the reader to come up with their own, new ideas, inspired by the text.

This misconception that summarising and experiencing can be equated is, in part, due to our unhealthy obsession with plot. I used to think that a good, complicated plot was necessary for a successful story, and it took me a long while to realise my mistake.

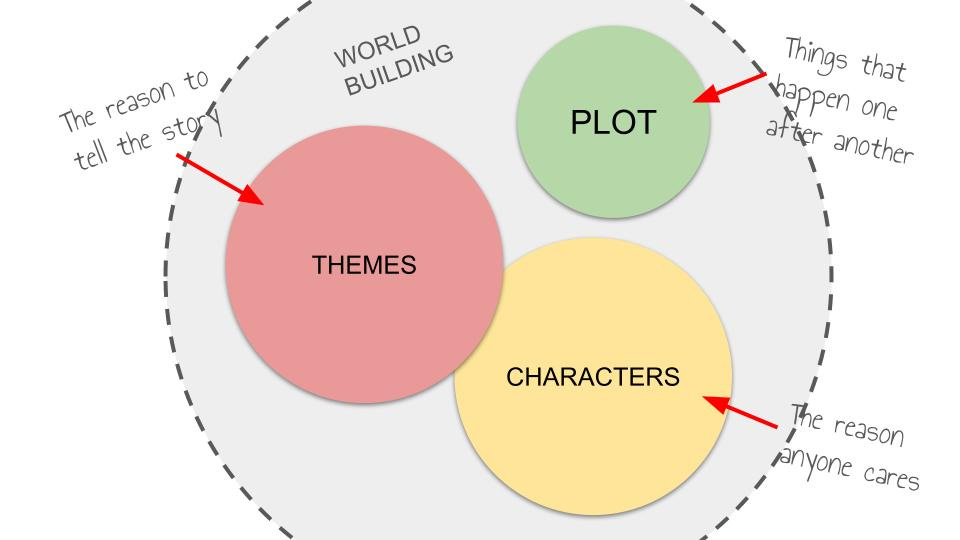

I now tend to think of plot as being the least important part of a story:

Plot is a sequence of events, which are rarely interesting in isolation. Themes by themselves can be the source of endless debate and compelling characters will captivate you even if nothing in particular is happening. But plot? Plot by itself is boring. (I go more into story construction here)

That’s the problem with skipping the text and only reading the summary. It’s living without meaning. One event after another, A, B, C, but there’s no point.

In large part this is because summarising a plot tends to ignore character and theme, or at least delivers them in a highly reductive manner. A long, convoluted plot can be reduced to a single sentence quite easily (“A simple hobbit walks a really long way to throw a ring into a volcano”), and it’ll make sense even if it misses the point. It’s not so easy to reduce a complex character or theme.

The quotes I started off with, from Mike and from Jack Clark, point to something else. Skipping straight to a summary cuts out perhaps the most important part of telling a story (fiction or non-fiction), which is when the intent of the author meets the interpretation of the audience. That’s when the magic actually happens. It’s why everyone has a different opinion of the same book, movie or song. The collision of creator and audience is generating something entirely new. There’s a chemical reaction taking place.

That’s why Mulholland Drive can be revelatory to some people and drivel to others. It’s why Titanic can reduce some people to blubbering wrecks, while others scoff at the dialogue. The source text is the same, but it’s the point of interaction that makes it into something special and unique.

It’s no use having someone else, or something else, simply tell you about it. Take any creative work and every audience member will have had a different and highly personal reaction to it. But send them all to a Wikipedia summary or an AI explanation and they’ll come away with a homogenised, borrowed viewpoint that represents a populist abdication of personal opinion.

(this is also why I get so annoyed with ‘explainer’ videos, that seek to replace individual interpretation with a unified, single Gestalt Take)

The viewing, or the reading, or the listening, or the playing, is the final edit in a long line of edits. The viewer, reader, listener or player is the final artist to work on the project. We each bring our own point of view, which in turn generates new ideas, exciting interpretations, more stories, real discoveries.

The real proof of all this is when we return to something, years later. As

put it:A movie we watched as a teenager reads differently as an adult. That same movie seems to be altogether changed when we watch it at 25 and then again at 45. Same goes for books, songs, everything. The source text has not changed, but we have: again, it’s that interaction, and the collision of the artist and the observer. If we relied entirely on generated summaries, or on other people’s recounting, we’d rob ourselves of that constant reinvention and re-experiencing. Which means we miss out on our own development.

Avoid being homogenised. Avoid becoming part of the Gestalt Take. Go to the source, and see what happens.

Meanwhile.

Over the summer I was inexplicably invited to the Substack Summer Party, which meant I was, at one point, stood a few feet away from

. I first encountered Ian’s swearing and amazing laugh on the Remainiacs podcast back in the 2010s as I was mourning Brexit. These days he has an excellent newsletter and the superb Origin Story podcast, among many other things (Origin Story’s recent episode on Enoch Powell and the Rivers of Blood speech is excellent).His latest post on AI, uncertainty, and how we’re all at risk of being reduced to inputs and outputs is a beautiful thing:

“Every article about AI has a picture of the Terminator in it, even though the film really has precious little to say about the matter. The much more pertinent film is Blade Runner. It has this aching sadness, this chilly rain-swept isolation, which is much more in tune with the future we're creating. What is that loneliness? It is the uncertainty every character seems to have about whether they are speaking to a human or a machine.”

I didn’t talk to Ian at the party. As well as being slightly starstruck, I was concerned that I’d end up in a detailed political or philosophical discussion that would reveal me to be a total idiot. When, actually, we probably could have just talked about Superman.

Other bits:

I’ve started playing Nier: Automata, which is a very weird, endlessly inventive and so far most excellent post-apocalyptic android game in which nothing is what it appears to be. The writing is all very on the nose, but has a certain charm:

We’re rewatching Arrow and Flash, this time with the 12 year old. Good fun, and it holds up well after a decade — in fact, by focusing on characters, and having the breathing room of 20+ episodes per season, it’s a template for how to avoid some of the problems superhero films have bumped into in recent years.

Talking of superhero movies, IGN published a small slice of sanity about box office numbers. It main point is to wonder why online discourse is so obsessed with financial numbers, instead of focusing on whether films are actually any good. There’s an odd type of armchair internet ‘critic’ whose only concern is to pit box office numbers against one another in order to declare success or failure. A certain type of person cares more about the franchise and the company’s bottom line than they do artistic merit. Which perhaps goes back to Ian Dunt’s point about the machines making all of us into robots…

I’ll park it there for today. Thanks for reading.

Some of their conversation still sounds a bit like an audio version of an Anthropic press release, as tends to be the case with coverage of AI. Lewis raises concerns about the impact of AGI, but there is very little in the way of interrogating whether AGI is actually likely. The inevitability of improvement is taken at face value, despite the diminishing returns from each version of ChatGPT.

"The viewer, reader, listener or player is the final artist to work on the project"- love this perspective! I totally agree, I have even found that the mood I am in when reading something will influence what I take from it.

I just finished reading a novel that left me kind of blah even though I read it straight through over the weekend. I enjoyed some of the characters (there were too many!), loved the themes, but hated the plot holes (my favorite character got no resolution). I went back and forth between rating it a 4 or 3. I finally settled on 3 after reading your article and understanding what I felt while I reading. Thanks again!