Possibly the best thing about writing a newsletter is how it facilitates meeting other writers.

I started chatting with

a couple of months back. Tim’s debut fantasy novel, Shadow of the Wolf, was first released ten years ago, with the trilogy only now being completed. He is traditionally published, but Tim’s route has been anything but simple.On the flipside, he was interested in the way I’ve gone about building my writing career.1 Writing online and in public, in serial form, and going straight to readers. We’ve come at storytelling from opposite ends, and have met somewhere in the middle.

In other words, we had to have a Proper Chat.

This conversation takes in the old versus the new, print versus online, pen and paper versus Scrivener. What can we learn from each other? Which way is best?2 What can we share that might be useful to new writers?

TKH: I’m excited to do this, Simon, thank you. I’m a great admirer of the work you bring into the world. Weekly serialisation is such an exciting format – I know readers who are following Tales from the Triverse must be thrilled when they see the latest instalment pop into their inbox. And your readership is growing. You now have, what, 4,000 subscribers on Substack? I know you started out on Wattpad, where you did very well, but this is a particularly fruitful period for you, isn’t it? How do you account for that? Are there things you’re doing differently to get your work noticed? What other factors are at play?

SKJ: Tim! What a pleasure. I used to produce a writing podcast in my day job, which was primarily an excuse to talk to writers in nerdy depth about their craft, and I’ve really missed those conversations. As such, I’m very much up for wherever this discussion happens to lead us.

Accounting for success – or lack thereof – in the world of books always feels like a roll of the dice, doesn’t it? Every “here’s what I did…” story is so unique to that person at that specific point in time that it’s difficult to transpose it in a useful way to serve as general advice for anybody else. That, I suppose, is why there are so many books and blogs and courses on how to write and how to publish. If anybody had actually figured it out, there’d just be a single instruction manual on how to do it.

At the time of writing I have precisely 3,797 subscribers, so not quite 4k but getting there. When I started writing on Substack in 2021 I had 129 subscribers, which I’d ported over from a mostly derelict Mailchimp list that I had never really used. So it may as well have been zero.

It’s quite difficult to understand and visualise large numbers of people. If I was able to properly grasp the idea of 3,797 people I’d likely never dare send another newsletter.

TKH: I should add, I know it’s far from only being about the numbers for you. You wrote a brilliant essay about how easy it would be to sell out, and how you’re actively working against that. It’s a tension I think a lot of creative people feel. And it’s encouraging, actually, to see how you’ve grown your readership organically.

SKJ: In terms of how I got from there to here, consistency is definitely a factor. And not giving up. Which sounds glib, but the main thing is that I’ve just kept going. The biggest differentiator between ‘successful’ writers and ‘unsuccessful’ writers is often that the successful ones didn’t stop.

All that said, my publishing online was never really intended to be about finding readers. At the start it was a trick more than anything; a last-ditch attempt to get my brain to actually knuckle down and produce something.

But let’s talk about your route, as well. You’re published by David Fickling Books3, a publisher very close to my heart because of their incredible commitment to publishing high quality books and comics for young readers.4 I was really excited to discover that you were published by them.

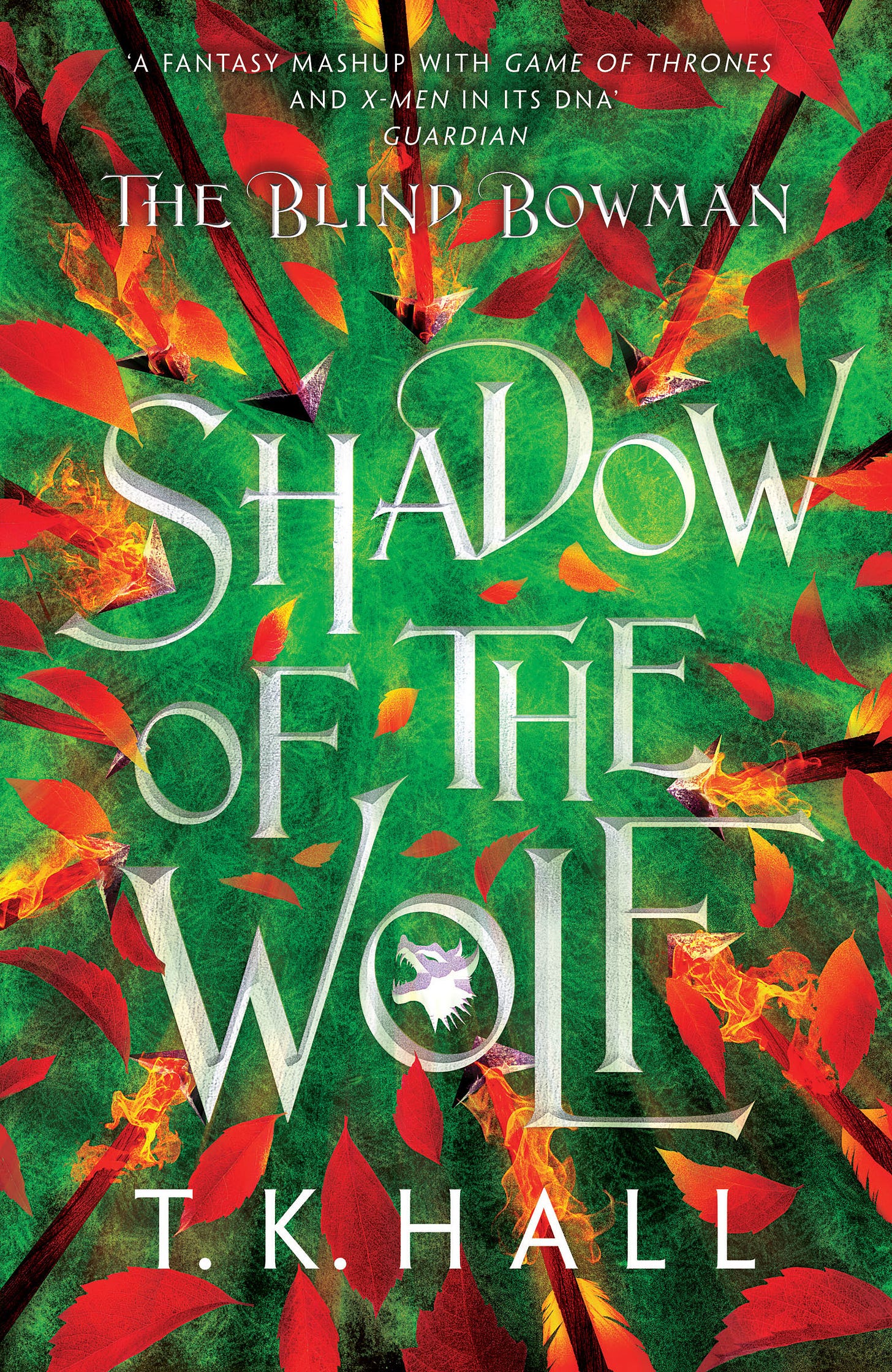

I have a lot of questions, so knowing where to start is the challenge here. But the elephant in the room, if you don’t mind, is hiding on the copyright page of Shadow of the Wolf. The current edition – which is beautiful, by the way – has just come out, with the trilogy sequels arriving over the next year, and yet the book was originally published in 2014.

Your debut came out ten years ago, and now here we are, at last, with the story about to be continued, and a fancy re-release. The question, then, is: why the gap? And, perhaps more importantly, how did you get from there to here?

TKH: Consistency - and not giving up. Yes, I can see you’ve built something over a long period of time, and those attributes must have been essential. I’ve had to dig pretty deep too. As you say, my debut novel, Shadow of the Wolf, a dark fantasy retelling of the Robin Hood legends, first appeared ten years ago. The publisher bought the rights to two sequels. Unfortunately, completing them proved beyond me for a long time. I was overthinking everything, planning and plotting rather than getting words down on the page. Or I was writing and writing but judging it all not good enough and scrapping the lot.

The causes of this blockage are complex. I’ve written about them a fair bit in my early Substack posts. One factor I’ve not ever really talked about, though, is the pressure I felt working with a publisher like David Fickling Books. As you say, DFB put out some wonderful stories, and are renowned for the care and attention they pour into every title they produce. They’ve published giants of storytelling like Philip Pullman, and they created the wonderful comic The Phoenix.5 Then they released my book! And suddenly I felt this great weight of expectation - like I was going to let the side down unless my follow-up was a literary masterpiece. Somehow I felt I was competing with His Dark Materials!

Which is ridiculous, I know, but it was one of the reasons I froze. In the end, I sort of had to start again. I took a long hard look at how I was working and overturned everything, making radical changes to my lifestyle, my outlook, and my writing practices. And eventually it worked. I finished my difficult second book, Dark Fire, and went straight on to write the third, Wildwood Rising. DFB re-released Shadow of the Wolf earlier this year, and will publish the two sequels over the next ten months.

I’m proud of the books, but I’m prouder still of the work behind the scenes — everything I had to do to win the psychological battle to get my writing back on track. That’s partly why I started my newsletter. I’ve learned so much along the way that I think can help others overcome their own creative struggles.

SKJ: There’s a constant contradiction in writing, or any form of creativity, I think. On the one hand, if you want to get anything done you have to treat it like you would any other job or task, and just get on with it, and get the words onto the page. On the other hand, you simply can’t force it – at least, not if you want the end result to be any good. Sometimes it feels like we’re all walking on a tightrope between those two extremes: complete creative paralysis, or factory conveyor belt production with little artistry. And you don’t want to be at either of those ends.

I spent 35 years not being a writer. I wanted to be one, and occasionally would tell people that, but I never quite got round to it. I’d have occasional bursts, but it was never very good and was always far from being completed. The solution for me, it turned out, was less to do with the writing and more to do with the publishing. I first tried serialising in 2015 with a story called A Day of Faces,6 and something clicked into place. Even if it was only a single reader, knowing that someone was waiting for the next chapter kept me coming back to the page, consistently, and I’ve kept going ever since.

TKH: I just want to say I think that’s great. It’s so common to dream and dream and not get around to doing anything about it, but to throw yourself in and build such consistency is amazing. And to think that the form — the method of distributing your stories – was so important. Some of my very favourite storytellers are what you might call ‘pulp writers’ — sci-fi authors like Jack Vance who called himself ‘a million words a year man.’ I suspect they felt the same urgency you describe – their readership waiting for the next instalment, which they had to deliver. I always dreamed I might be a ‘pulp writer,’ actually, knocking out stories for magazines and cheap paperbacks (ironic really because so far I’ve ended up doing basically the opposite - spending over ten years crafting a few finely-produced books!) I still think there’s something really romantic in what those 70s sci-fi and detective novelists were doing – storytelling not as some lofty thing but as thrilling immersive wondrous stuff that people really want and love. And I wonder if you’ve found the modern equivalent publishing on Substack. Certainly it seems to be working for you and your readers.

SKJ: We’ve both been on little adventures while trying to figure out how to write, it seems, and have needed to find our way back to the path. Albeit quite different paths!

That sense of pressure you felt, of suddenly needing to match up to Pullman, and of being alongside amazing artists at a respected publisher, and how it induced a negative effect on you, is interesting to compare with my experience. For me, the pressure of having readers was a positive and helpful thing. The difference perhaps is that my readers wanted more but I never had a sense of being judged, of needing to hit a particular quality bar. The route I took was under the radar and low stakes, in part because it was inherently amateur (by which I mean ‘not a paid job’, not ‘bad quality’). Whereas you had been thrust straight into the professional book world, all eyes on you, reviews in major newspapers, books on shelves. People paying to read your work.

TKH: One of the many things I was keen to talk to you about is your relationship with social media, and technology in general. I have a feeling it’s healthily ambivalent. On the one hand, Wattpad and Substack have been great platforms for your stories. On the other hand, you’ve shown concern over Midjourney and ChatGPT. In fact you’ve made the declaration: “Everything I publish is created by humans.” There are further warning signs in your superb novel No Adults Allowed. I don’t want to give too much away, but the omniscient AI in the story initiates a ‘Clean Sweep Protocol’, which is as plausible as it is chilling. The overall impression I’m getting is an author who stands right at the interface, excited by the possibilities, yet also a little afraid of the coming wave. Is there any truth in that?

SKJ: I’ve always loved technology and computers, from the mid-80s when I was a child. I’m the sort of person that jumps on new systems early and pokes at them to see what they can do. That was the case with MidJourney in 2022, which I found utterly astounding and hugely exciting: suddenly I could illustrate every single weekly chapter of Tales from the Triverse to a high technical standard! It was thrilling.

A few months later ChatGPT appeared, and I was rather horrified. An AI was daring to take away my writing? Outrageous!

The hypocrisy wasn’t lost on me, and it prompted a lot of agonising over what I really thought about generative AI. At the same time it was becoming increasingly clear that the corporations in charge of these AIs have been scraping data for years without permission. The ethical fog combined with the ongoing copyright fuzziness would have been enough for me to pause my use of AI generated images, but there was another, more pressing factor:

AI content becomes boring really quickly.

Since using MidJourney I’d done less of my own art. I’m very much a beginner artist, but I slowly realised that I was leaning on MidJourney. I missed doing my own illustrations, and decided that my readers – the ones who enjoy reading the words that I create – would probably prefer a shonky drawing that was mine than a perfect illustration that was AI generated. No matter how snazzy the AI image, it was ultimately hollow and meaningless. An illustration by my own hand would be technically vastly inferior, but my personality would be all over it, for better or worse.

That’s where I’m at with AI, as of 2024. Generative AI, if anything, has only become more boring in the last year. So much of it, including images used by indie authors, is instantly recognisable and I tend to avoid reading anything that includes an identifiable AI illustration.

At some point the AI hype bubble will pop, and in the aftermath we might see some more interesting use cases emerge. Or possibly not, according to Cory Doctorow.

My relationship with platforms such as Wattpad and Substack is much more positive. It’s not exaggerating to say that without them I wouldn’t be a writer. We can get into that a bit more, and the role Wattpad in particular played, but first: while we’re talking about technology, we should explore your big switch from the screen to paper. I was fascinated by your article about going freehand, because it’s something I haven’t done and can’t imagine doing. Though your piece goes a long way to convincing me to give it a whirl.

My question, then, is about your relationship to technology with regards to your writing. I sense that it’s got in the way more than it’s helped you?

TKH: I don’t know if I’m instinctively wary of technology, or it’s something that’s been growing on me, or both. It’s certainly true I’m something of a dinosaur. If I can get away with it, I’ll leave my phone off for long periods of the day, which I realise is quite unusual. And yes, a couple of years ago I went back to drafting freehand with pen and paper, and I think it really helped unblock my storytelling. Even when I transcribe my drafts I do it onto an ancient non-networked desktop that can do nothing but word process!

SKJ: That sounds quite idyllic. Because I’m inherently a techie at heart, I’ve long been tempted by these things called Freewrite, which are like basic typewriter devices. Designed for writing without distractions, but still with the benefits of typing and digital storage. Mike Sowden (fellow newsletter writer extraordinaire) sings the praises of the Remarkable tablet, too - a natural writing tablet that looks like a great marriage of digital convenience and old school freehand. Unfortunately it costs about a billion pounds, so I’ll need a few more paid subscribers before I consider that one.

Maybe one day.

Or perhaps I should just get a £5 lined notebook and a biro.

TKH: Ha, yes. Like you say, every writer is unique in what works best for them. I think the important thing is to experiment. Try scribbling on post-it notes. Try dictating your story. See what happens. Does your storytelling improve, or get worse? It will almost certainly be changed by the method of composition. It’s surprising but true. Even altering the size of the font on your word processor can make you think differently and therefore write differently. For me, over the years, I’ve come to learn that my storytelling works best in a contemplative state not so different to meditation. Anything that intrudes into that space only makes the work harder. Therefore the basic pencil and paper approach suits me best.

SKJ: Absolutely agree with all of that. It must differ so much for each writer. For me, freehand writing is part of that intrusion: for me, it’s so slow and cumbersome that it gets in the way of translating my brain into words. But you’re completely right: it’s so critical to strip away anything that distracts or gets in the way of the writing, whatever that may be for the individual writer.

TKH: And technology, increasingly, has become so shouty. It all wants your attention, and it all wants control. So yes, like your experiences with Midjourney - it wants to take away your drawing! Your drawing is a pleasure, to yourself and others, even if, perhaps partly because, it isn’t machine-polished. It’s really interesting that in the end you found AI creation - and indeed the finishing articles - to be boring.

SKJ: The thing is, until the last 10-15 years, technology has been primarily about solving problems and helping people to do things. The internet was that for a long while, but has morphed into a bizarre time sink that doesn’t serve any real purpose. Even the early days of Facebook and Twitter had a purpose, in that they connected people in quite exciting ways, on a global scale. The corporations have slowly transformed them into platforms that do everything except that core purpose: they exist to distract us and stop us from doing things. It’s quite nonsensical.

I make a firm distinction between technology like Scrivener, which exists to be a tool for humans, and distraction platforms like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and so on.

TKH: That sounds like a really useful distinction. Yes, the more we can be conscious of technology as tools we can choose to use, rather than as something we’re obliged to indulge, the more we free ourselves to be properly creative. What’s more, part of me wonders if we’ll always be able to tell the difference, on some instinctual level, between something made by humans and made by machines. I hope so.

SKJ: It’ll only properly get to the point of us not being able to tell the difference if machines achieve actual sentience. And that’s a completely separate thing to what the LLMs are doing at the moment. If an AI achieves proper sentience, that means it will have a point of view, and then we’re into a completely different – and far more interesting – discussion. Assuming it doesn’t try to murder us all.

TKH: Mind you, for all my reticence about technology, I’m trying not to live too much in the past. We are where we are – this is our time and our world to live in. If I want my work to be seen, and my books to be read, I recognise that I need to have some kind of online presence. It’s early days, but I hope I can find a balance. I suppose we’re all trying to find that. To shift topics slightly, I wanted to ask you about your productivity. You publish a substantial body of work every week: serialised fiction and essays on craft. I know you also have a full time job and a family. How do you manage the workload? Does the technology aid you in that, or make the juggling act more difficult? Do you have particular habits and routines that keep you on track?

SKJ: For starters, I’ve built up to this current level of output over a very long period of time. I started writing serials in 2015, and I did one chapter per week. That first book was quite simple, too: it was told in 1st person, so had a single narrative voice, and was very forward-facing in its plot. Over time I’ve tried writing more complex stories: more characters, deeper themes, more detailed plots, just longer.

I moved over from Wattpad and started writing the newsletter in 2021, so that was six years in. I was confident by that point in my ability to serialise a chapter of fiction each week – that’s what Wattpad had shown me. Adding the Monday non-fiction ‘tips’ newsletter was the next challenge, and so far that’s gone quite well. I do use the occasional trick, such as starting a discussion thread in which readers can share their own thoughts and insights – which gives me a bit of breathing space.

Tech does help to a degree. Substack makes the whole thing possible, in terms of building a list, growing it, sending it out, without it becoming impossibly expensive. Scrivener is really my secret weapon, though. I’m confident in saying that I couldn’t write weekly serials without it. It doesn’t help me be a better writer, but it absolutely helps me be a more consistently productive writer.

TKH: Wow. I need to go and watch your popular video on how to use Scrivener. I’ve been a bit scared to in case you persuade me I need to use it and ditch the pen and paper! Mind you, it’s probably like we said before: different tools work for different writers. Your weekly format is perhaps perfectly suited to an all-singing piece of kit like Scrivener.

SKJ: Going back to your trilogy being completed at last: having not worked with a major publisher, I’m intrigued that DFB have not only stuck with you while you were battling your blocks and finding your way back to the page, but they’ve re-released Shadow of the Wolf in a beautiful new edition with a really stunning fresh cover. You’ve also had the opportunity to do something of a ‘director’s cut’ reworking of the text, too, is that right?

I don’t know what you can or cannot say, but I imagine it was a tricky road based on the publisher’s original expectations – yet it’s ended up in a really positive place for all concerned. How did the re-release and the readying of the second and third books come about?

TKH: Yes, I’m very grateful that DFB stood by me and had faith in my story even when it was lost in the woods. It did cause us all a bit of a headache, but we managed to stay friends and to find our way back to a good place. I think actually that’s one of the great things about DFB being a relatively small independent company: they can make decisions based on artistic judgement and integrity rather than always being ruled by publishing schedules and the bottom line. My new editor at DFB, Anthony Hinton, has been particularly instrumental in reinvigorating my series, The Blind Bowman. Like you say, even after years of delay, he gave me the green light to go back and revise the first book ahead of its re-release. I think that’s the kind of thing a big publisher wouldn’t have been able to envision because it wouldn’t tick the right boxes. DFB are obsessed with making their stories as good as they can be, no matter how long or painstaking the process. So yes, I’m really happy to be working with DFB, and I’ve already started talking to them about my next series, which is very exciting.

Although, having said that…I’m so intrigued by this Substack platform, and particularly the way you use it, that I could definitely imagine serialising my future stories, or perhaps looking at a combination of online and traditional publishing…who knows!

SKJ: That’s the best aspect to all of this — ultimately it’s about writers having more options, and being able to pick and choose which one is right for each project. Writing is never easy, and publishing is always hard, but I feel that we find ourselves in especially exciting times.

TKH: I couldn’t agree more. And this chat has been every bit as enjoyable and enlightening as I thought it would be. I hope we get to collaborate again in one form or another. Many thanks, and keep up the great work!

T K Hall is the author of the acclaimed fantasy novel Shadow of the Wolf, together with its forthcoming sequels, Dark Fire and Wildwood Rising. Thus far, he has gone down an entirely traditional route, his work appearing in hardback and paperback. His publisher is David Fickling Books, a legacy imprint based in Oxford, which releases a small number of carefully crafted titles each year. His first sustained engagement with social media is his Substack newsletter, Wildwood Rising, which he started at the end of 2023

Thanks for reading!

In other news:

I was amused to be included in the latest

feature announcement thanks to my video of very noisy frogs.

Lots of useful bits and pieces on building a subscription base for your writing in

’s recent round-up, which you can find here.An interesting note from

that I’m still pondering:

The Babylon 5 rewatch continues, if you fancy joining us:

Quick reminder for anyone in the East of England that I’ve got a couple of author events coming up in May. Building a Presence Online with the Society of Authors on 18 May is going to be very Substacky. And if you’re in Suffolk, do come say ‘hi’ at Halesworth Library on 23 May.

That’s about it for this week. Hope you enjoyed my chat with Tim, and don’t forget to check out his newsletter:

If you can call it that.

Spoiler: neither!

If you have a child under the age of 15, immediately stop reading this and go get a subscription to The Phoenix comic. Trust me.

Told you. Have you subscribed yet? Come on, hop to it.

Currently this one is only on Wattpad, but I have plans.

Fascinating. Thanks to both of you.

Great interview. I liked the discussion on technology, the tension of being creative, the importance of consistency and more. Appreciate you posting this.