Writing from a limited, subjective point of view

It's all about what they don't know

Choosing the point of view for your story is the big make-or-break decision. You have to figure this out ahead of time, because it directly affects every aspect of the text. It’s not really something you can decide upon while writing.

Everything else can be tweaked and adjusted as you go. Character arcs, plot beats, themes. But the point of view is the translation layer between what is in your brain and what ends up on the page.

Most of my serials have been written using a third person narration, with a limited and subjective point of view. Scenes are told from a single character’s experience, with knowledge, sensory impact and attitudes tuned to the narrator character. In Tales from the Triverse I often hop between characters within a single chapter. An earlier serial, The Mechanical Crown, was stricter, with a single POV character per chapter.

The stories I like to tell tend to be large in scope and feature ensemble casts. A third person limited POV lends itself to that structure.

This article has a succinct summary of the history of POV in novels.

As a child, most of what I read was told from a more omniscient perspective. There was an additional narrator character, who existed off-screen and was recounting events. They knew everything and could provide insight into any character, and even directly address the reader.

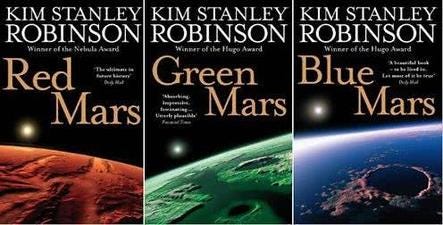

The first time I really noticed a limited third person POV being employed was in Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy. It’s very strict in its structure, going deep into a single character’s perspective for extended chunks.

I’m sure I’d encountered this style of narrative in books previously, but Robinson’s trilogy was the first time I’d actively noticed it. He hadn’t written in this narrative form simply because it was what everyone else was doing. He hadn’t stumbled into it by accident. It was evidently a deliberate choice, applied with precision to the story being told.

Many years later, another KSR book again caught my attention for its clever use of point of view. Galileo’s Dream might be my favourite of his works, and it’s quite a departure from the Mars trilogy.

[spoilers incoming] Galileo’s Dream begins as straight historical fiction, detailing Galileo’s life, and would be an excellent book if that’s all it was. It’s told in a fairly standard third person. There’s a moment a fair way into the novel where there’s an abrupt use of first person, and the previously invisible narrator becomes diagetic, shifting from a position of detached omniscience to being rooted within the story itself. It’s a startling moment which flips the story on its head, and it’s done with a quiet subtlety that could be easily missed if a reader wasn’t paying attention. The narrator then becomes an active player in the story.

I love that this twist is done not through plot or dialogue, but by an unexpected shifting of the narrator’s point of view.

The real joy of a subjective, limited point of view narrator is in the friction between what characters know and what the reader knows. That’s often where I find the real joy in writing, constructing towers of tragic irony that come tumbling down at inopportune moments. I imagine my readers screaming as character blunders their way through the story with limited information, unaware of what’s really going on and what’s about to hit them in the face.

Or, as

, winner of the recent sci-fi Lunar Award puts it:Examining my writing in the least romantic way possible, Tales from the Triverse has, at times, been an exercise in carefully timed information dumps. A more omniscient narrator (unless specifically unreliable) makes the twists and turns of a conspiracy-laden story trickier to manage. For all its sci-fi and fantasy trappings, most of Triverse is wrapped in a crime fiction layer, which becomes especially effective when characters and reader are kept slightly in the dark.

At the beginning of a story, the reader has very little information. Over time, with multiple limited 3rd person viewpoints, the reader will begin to form a more complex understanding of the situation, with each character/narrator a piece of a larger puzzle. By the time the reader reaches the climax, they will be picking up on subtle cues and hints about what is happening, how characters are motivated, and what might happen next — all without any of it needing to be stated in the text.

That is perhaps why I find it so compelling to write in this way: it’s an efficient technique for show not tell. By juxtaposing the unique viewpoints of multiple characters, with their idiosyncrasies, prejudices and assumptions, a story is built that resonates and feels more sophisticated than its individual components.

Point of view is on my mind because I’m in the ‘big finale’ stage of Tales from the Triverse. It’s the part of the story where all the threads and characters from over three years of the serial have to coalesce in a way that makes sense, and which serves as a satisfying ending to all that’s come before. As such, there’s a lot of POV jumping going on, lots of hopping around locations and scenes.

And so I have scenes from the POV of Clarke and Kaminski, two of the detectives who have become lead characters. They’re both caught up in events far bigger than themselves, and are responding quite differently — while still working together towards a common goal. They’re not ‘heroic’ characters, which makes their heroism all the more compelling. But I’m also jumping to antagonists, and finding out what is motivating them during such heightened times. Crucially, it’s a chance to show their motivations, and how they see themselves as the heroes. Each POV shift is a chance to undercut what’s come before, or reinforce it, each time shining a light on events from a different angle.

POV being on my mind prompted me to post this a couple of days ago, which is related to what I’ve been writing in today’s post:

You tend to see a lot of talk of how different storytelling modes have moved in and out of popularity over time. The omniscient narrator being very popular in the classics, but falling away in the 20th century. The rise of more subjective and limited perspectives.

But, really, it’s always about picking the right approach for the story, as

pointed out:Why some perspectives work better than others for certain stories I find endlessly intriguing.

has a fairly firm opinion on the matter:Then again,

noted:I tend to write fiction that is easy to read, I think. I want readers to settle into my stories easily, and be entertained. If there is challenge, I want it to be in the themes and the questions raised, rather than in the prose itself. But Victoria’s point is that challenge in the language itself can contribute to what a story is trying to achieve.

The general consensus in the discussion was that 2nd person is easier to work with, and read, in shorter works: poetry, songs, short stories. Even in games, where it’s very common, the writing is usually broken up by interactive elements where the player will be doing something other than reading.

Maybe

is on to something:My first book, and first published serial, was A Day of Faces, told in the first person POV of a teenage girl. I was far less experienced back then, and while Kay was a compelling character and I loved writing her voice, I quickly bumped into problems with the structure. The story I was trying to tell was larger than the tight first person POV could convey.

I ended up fudging it a bit, with third person interludes at key moments. It was a cheat that I’ve never been happy about. That’s why nailing the narrative framework of a novel is so critical, especially if you’re writing and publishing a live serial. I didn’t have a good handle on where A Day of Faces’ story was going, which is why I employed a structure that didn’t entirely fit. In pre-production on Tales from the Triverse I mapped out exactly what I wanted the story to be, which dictated how the narrative would be formed.

Anyway, that’s me. How about you? Do you always write using the same approach to POV, or do you change with each story?

Meanwhile.

This morning I listened to the Triple Click podcast, which featured writer Tom Bissell. Tom’s written for all sorts of games and also happened to write the final three episodes of Andor season two.

Needless to say, Tom has lots of very clever things to say about storytelling. Highly recommended listening, even if you’re not into a) games or b) Andor.

We watched Ironheart, the latest Marvel TV thing. It’s a big ol’ mess, which is a real shame as all the ingredients are in there for something fun. Its main problem, I think, is that the lead character Riri Williams has no real character arc. There’s no progression: she makes one bad decision after another, never really learns from any of them, only vaguely sees consequences of those decisions, and the show itself never really grapples with or even acknowledges that the decisions are being made. This is made more confusing by the show repeatedly stating that Riri is a genius, without ever demonstrating those smarts. She can build highly complex robotic exoskeletons and AI, but her inventions seem to come about more through hand-wavey magic than actual science or engineering. That’s possibly why the second half of the show, which goes more into actual magic, works slightly better.

The 12 year old is also working his way through the Marvel movies, many of which he saw when he was quite a bit younger. That resulted in us watching Black Panther yesterday, which made for quite a stark (lol) contrast with Ironheart. Black Panther’s script is incredibly tight: there’s a typical macguffin in the form of vibranium, but they cleverly put that in the back seat and stay focused on character, culture, politics and interesting stuff like that — but without ever forgetting to have amazing action sequences.

Right, hope you all have a good week. I’d better get back to wrangling Triverse.

Thumbnail Photo by Petri Heiskanen on Unsplash

Glad to see you continue with this POV theme because it is one of my favorite aspects of creative writing, whether fiction or non-fiction. Even though my work is written in third person past tense as per popular genre fiction conventions, when authors dare to bust out of this POV box, it's pretty neat and really adds energy to the readers experience, IMO.

Wolf Hall is my favorite all-time novel precisely because Mantel turned the third person convention on its head by using it in the present tense. It is astounding how immediate the writing is. How the reader actually "becomes" Thomas Cromwell; moreso than with first person. I've always thought immediacy of character experience for the reader is the pinnacle of storytelling and she nailed it.

Thank you for your mention in today's post. Great discussion.

Bearing in mind I’m focused on personal improvement/business change as my column. I’ve had some helpful tips from Alison Acheson about the use of “voice”. Specifically aiming at some 4th wall to audience commentary with humour. I’d be interested in any thoughts on the relationship between voice & person. Ie 1st, 2nd, 3rd… & how it could work.