Third acts and meaningless spectacle

How can we do a big finale that people still care about?

Heroic characters tend to provide diminishing returns. We are often drawn to origin stories because they provide a built-in character arc, where development is part of the package. Once they have reached that apotheosis, going from ordinary person to hero, what then? Often the response is to ramp up the action and spectacle to ever-more absurd levels — and dwindling audience engagement.

As someone who is currently writing the closing stretches of a long-running serial, in which the story has escalated to the point of world-level threats, all of this is very much on my mind. It’s a challenge anyone working in genre fiction is going to bump into at some point.

This has been on my mind since reading

’s note a few days back:How many times did critics review a Marvel film back in the glory days, generally like the first two acts, but lament its inevitable descent into crashy-punchy-bangy CG action for the finale?

Why is it that some action-oriented stories keep us engaged to the end, while others feel like they’re going through the motions? Why is this problem especially prevalent in movies? And, most importantly, how can we as writers avoid our stories falling flat?

People power

My theory, which won’t come as a major shock, is that it all comes down to character development.

There’s a reason that literary fiction doesn’t tend to bump into third act problems. When was the last time you read a literary fiction novel where the spectacle or world-ending stakes left you disengaged in the story? Right, so litfic doesn’t tend to play in those particular waters in the first place, but to focus on the spectacle and action and visual effects (on the page or screen!) is to slightly miss the point.

The spectacle of the third act in genre fiction isn’t the culprit here. It’s part of it, but spectacle in itself is not problematic. Where stories come unstuck is when the focus on being epic distracts the writer away from the characters.

Literary fiction, to generalise massively, tends to utilise smaller scale narratives. The scope and excitement comes from a more internal space, one that is driven by characters and what’s happening in their heads. A chase sequence or massive spaceship battle is probably not going to happen in the finale. Litfic can still have similar beats, but those moments are mapped more directly to the people in the story, rather than to plot events. As long as you’ve been engaged by the characters in the first half of the book, you’ll probably continue to be so through to the final page.

Genre fiction does quite like big spaceship battles, armies of orcs and elves crashing into each other and rooftop chases in order to stop the bad guys. So why is it that sometimes it’s thrilling stuff, and other times it’s formulaic and dull?

Let’s poke at this in more detail. There are specific traps to watch out for, and techniques that can be used, to have your cake and eat it: it’s more than possible to have the big action finale while keeping your readers fully engaged with what’s happening.

Foundational motivation

Cae mentioned this one in their original note. The Lord of the Rings takes its time to establish the status quo, and demonstrate what everyone is fighting for.

Most obviously this is with the hobbits in the Shire, where we see Bilbo and Frodo having a lovely time in a cosy house, having parties, going down the pub, reading books under sun-dappled trees, digging up potatoes and the like. Everyone is having a lovely time (except that really grumpy scowly guy).

The book goes even further, spending a surprising chunk of Fellowship of the Ring faffing about in the Shire, literal years in story time, before Frodo and Sam head off on their actual quest. By the time they get on the road, we know what they’re defending, and we also know that these are not your typical questing heroes.

All the way through the story, the hobbits’ primary motivation is to get home and go down the pub. Sure, they’re committed to saving the world and stopping the Dark Lord Sauron, but the reason they’re doing that is so they can go down the pub. And, critically, so other people can choose to go down the pub as well.

At no point do they crossover into doing heroic things because they are heroes. Even the characters that are more traditionally heroic, such as Aragorn, are filled with melancholy and regret and doubt. Heroism is thrust upon them, and they accept it reluctantly and awkwardly.

A version of The Lord of the Rings movies in which they shortened the Shire section would not have worked as well. It’s the anchor for the rest of the trilogy, even when they find themselves on the side of a volcano surrounded by orcs and fire.

This is why origin stories, especially in superhero fiction, tend to be easier to pull off. By definition, they start before the hero is a hero, and the world is at rest. We see the normal world, the world they are going to end up saving in some way. It might already be broken and they’re going to fix it, or it might be Shire-like and need protecting. The character arc shows them becoming able to do that.

Following up on an origin story is when it gets tricky, because the most important part of that character’s life has already happened. Nothing in Peter Parker’s life is as consequential as being bitten by that spider.

(tangential rant: this is why the film Solo doesn’t really work. It thinks it’s the origin story of Han Solo, but that has already been told: that’s what happens in Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, as we see him go from callous, amoral smuggler to rebel hero — that’s the pivotal moment in his life. The film Solo is actually an origin story for random material objects that he owns, and which are generally unimportant)

Keep your action heroes fallible

OK, so origin stories are easier, because they have character development built-in. A lot of stories are not origin stories, and even those origin stories tend to wind up with sequels. So what then?

A mistake a lot of genre fiction makes, especially across film and comics, is that characters become entirely inured to the situations they’re in. It becomes rote and commonplace to them, whether it makes sense for the characters or not. How many action films involve an ordinary member of the public getting accidentally embroiled in criminal antics (probably alongside a cop), but by the end they’re miraculously comfortable with the whole ordeal? Also common is for a character to die, and then be forgotten by the end of the movie — a plot death to serve as motivation, but without any kind of relatable response from the survivors.

All too often, characters forget their situation and slip into Action Hero Mode. This makes for very boring characters. Action Heroes are people who can handle anything, never suffer, never pause to consider the insane situations they’re in. This can work if you make a point of it, but a lot of adventure writing slips into this mode without even realising it.

Die Hard is a classic for several reasons, one of them being that John McClane never stops being a normal bloke. He ends up doing crazy things that no ordinary person would survive, but his behaviour, his decisions, his dialogue, remain rooted in the character we met at the start. He’s tough as nails, but he never quite believes the situation he’s ended up in. And, like the hobbits trying to get down the pub, all he really wants to do is reconcile with his wife and have a nice Christmas.

It’s interesting to look at the films that came out in the 2000s, in the wake of The Matrix. They learned the wrong lessons from that film, thinking that it was all about being cool and aloof and wearing shades while in slow motion — affectations that plagued action cinema for the rest of the decade. Neo in the first film is messy, flawed, in disbelief throughout, never knows what the hell is going on and makes mistake after mistake. He only becomes an Action Hero in the very final scenes of the movie, because that is the point: he only becomes an Action Hero (‘The One’) when he believes he can be. If he’d hit that point earlier in the film, it would have been less engaging (and is probably why the sequels don’t quite work — again, Neo has already been through the most important character arc of his life).

To move away from cinema, Iain M Banks’ Culture novels do all sorts of interesting things to balance action, spectacle and character. Describe key moments from Consider Phlebas or Use of Weapons and it could sound like something from a Star Wars film, but Banks always finds a new twist on an idea. He eschews any pursuit of ‘cool’ (as seen with those post-Matrix movies) in favour of exploring ideas and motivations. As with anything, trying to be cool is the fastest path to being uncool, and Culture books thereby end up having a style all their own. The outrageous action in Use of Weapons is all there in service of character (in ways not always immediately apparent), rather than to further the plot or provide basic excitement.

This is How You Lose the Time War juxtaposes incredibly high concept science fiction with a very grounded love story, told in epistolic fashion. The two characters are writing letters to each other across time and space, but the world-shattering events are no more than set dressing. The spectacle is in the background, slightly out of focus, while the story remains fixed on the odd pairing of the two leads. A cinematic rendition would show them doing epic, adventurous things, which would rather take away from it: they don’t care about their jobs, and have thoughts only for each other.

Remembering your roots

I often come back to a quote from Ryan Coogler, when he was directing Black Panther, talking about how he didn’t quite believe in Wakanda as a real place until they filmed a scene in a food market. Seeing people eating and doing Normal Stuff was necessary to create the required verisimilitude.

This is often forgotten in genre fiction, especially as plots whirr into high gear. No time is left for people to just be people. At the start of a story, writers are more likely to include scenes of characters hanging out, going to the shops, being in a bar, seeing friends. All of that becomes more distant as the speculative fiction elements become more apparent, as if the two cannot co-exist.

Even Deckard eats. Blade Runner is chock full of memorable scenes, but the one that is the key image from the film for me has always been the food market, at night, rain-slick with steam pouring from vents. Dirty, sodden, but full of culture and life (real or artificial). It’s those scenes which elevate the film above being an action flick about hunting bad robots.

In stories that tend towards heroic action, these scenes become even more vital. They’re the ones that remind the reader and the characters of what is at stake. It’s important to see The Real World, because otherwise we end up stuck in an entirely fabricated space that is divorced from any kind of reality.

I suspect the Spider-Man films have continued to be successful in part because Parker has normal friends, who continue to be supporting characters throughout. They still go to school, try to get jobs, go on school trips. Parker has to be Spider-Man in and around that. It’s all too easy for action and genre fiction to forget about the mundane, or to give the heroes any kind of downtime: it creates a relentless pace and misses out on opportunities to explore character in a range of scenarios.

I’ve decided to call this Fantasy Drift. This is when a long-running series slowly becomes divorced from reality, or a sense of reality. It perhaps starts in the real world, or at least in a fantasy world that has time for the depiction of normal life. Over time, the heightened drama pulls the main characters further into the plot, and into Deep Lore, and it becomes entirely about their new lives in Adventure Land. The anchors are cast away, the story becomes unmoored, and readers and viewers lose any reason to care about anything. We don’t care about a Bad Guy trying to destroy the world unless we know the world.

A sprinkle of the mundane can go a long way to rooting the fantastical.

The fantasy soap opera

A curious quirk of popular fantasy fiction is when it goes so all in on spectacle and scale that it becomes almost entirely divorced from reality, then leans into it as a virtue. This is a scale issue and can be seen with both Marvel and DC comics, whereby the roster of characters is so immense, the lore and backstories so detailed, that the writers rarely have any cause to dip into the ‘real world’.

All the drama can come from the interplay of the main and supporting cast, all of whom are super-powered beings. They live in Avengers tower (or inside a dead Celestial, to take some more recent comics), physically removed from the real world. Their interactions are with other super-beings, cosmic and inter-planetary. They pull in sci-fi, mysticism, magic, fantasy, adventure, spy — every genre you can imagine. The characters occupy a weird elitist position, above the rest of society.

Often the ‘extended universes’ depicted in these mega-franchises are entire alternate realities with only a veneer of the real. Sometimes that can work, if a reader is fully into the complex relationships of the X-Men. It can be overwhelming and confusing for anyone dipping a toe for the first time: good luck to anyone who tried to pick up a comic a decade-or-two back when the MCU movies started becoming mega-successes.

It’s superhero fiction as soap opera: a revolving, expansive cast, often within specific settings. Coronation Street and East Enders rarely venture away from their primary locations to explore the rest of the world, existing within their own bubble. That’s where superhero comics often exist. By embracing a complex web of relationships among a huge core cast, they bypass the need to establish the stakes, or have clear foundational motivations, or fallible heroes, or links to normality. All of that comes from within.

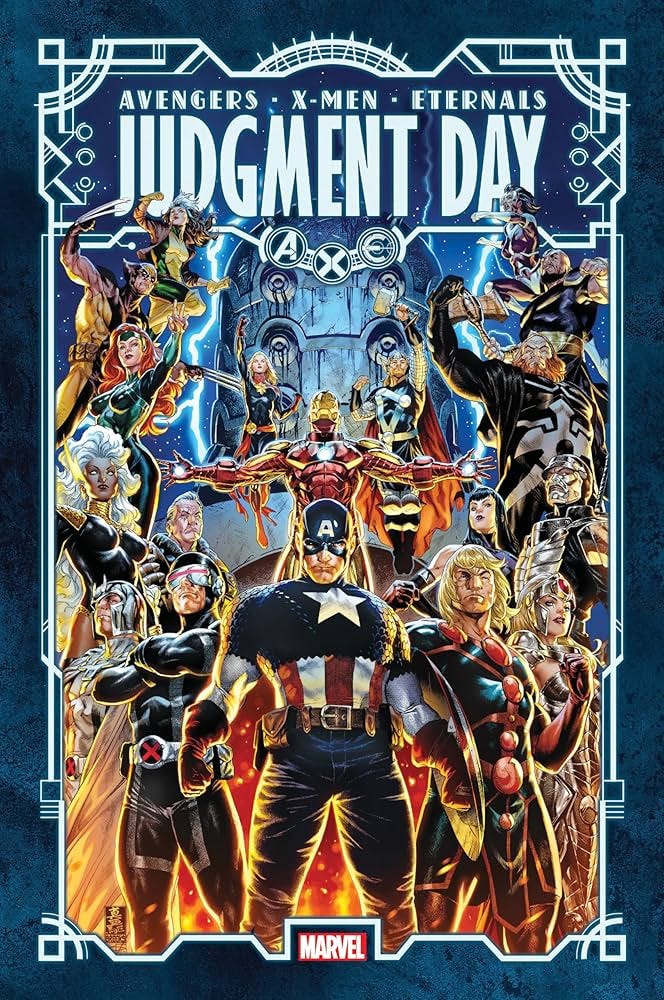

Kieron Gillen’s A.X.E. Marvel crossover event from a few years back was fascinating: a sprawling epic told across all of Marvel’s comics, perfectly positioned to fall into all the usual traps of a ‘crossover event’ — being impenetrable to new readers, lore-heavy and navel-gazing, and corporate-motivated in its story beats.

Instead, Kieron delivered something unexpectedly moving and memorable and weird. The big ‘event’ was the arrival of a Celestial being which is to pass judgement on every single person on Earth. The comic is a case study in how to create an engaging story even when dealing with Deep Lore characters: the judgement concept provides an excuse to dive into each character’s motivations and history in often unexpected ways, and the comic makes a point of judging ‘normal’ people as well as superheroes.

The key moment for me is the realisation that a gargantuan, Cthulhu-like abomination stomping towards a US city and destroying everything in its path is simultaneously exchanging internet DMs with a woman. She has no idea that she’s communicating with an elder being bent on destroying the world. It’s weird, poignant, and draws a direct connecting line between the mad spectacle and the mundane.

Gillen’s work in that run contains all the answers for how to craft epic scope with an intimate feel.

How to make an impactful finale

Let’s recap, focusing on the specific practical techniques we can all use to keep readers caring as we barrel into third act excitement.

It’s all about character. Your plot might be about an evil wizard trying to destroy the universe, but nobody really cares about any of that. No matter how big the action gets, the focus ought to stay locked on the characters. and how they are responding to events.

Establish the stakes early, and keep referring back to them. Why do the heroes care? What are they fighting for? Don’t assume the audience remembers, and beware of the characters forgetting. There’s nothing more boring than a hero fighting simply ‘because they’re a hero’.

Keep your characters grounded and fallible. Even if they’ve been drawn into crazy, world-ending spectacle, don’t allow them to brush it off as if it’s nothing. Pain, fear, doubt — that keeps characters interesting, and makes acts of bravery more impressive.

Embrace the mundane. Ordinary scenes, actions, thoughts are anchors for the audience; ways to empathise and understand what’s going on, even if the surrounding events are increasingly dramatic and fantastical.

These aren’t rules. They’re intended as useful tips, and there will be exceptions to all of them. If you’re writing big, speculative fiction these guidelines should hopefully help you craft a satisfying ending.

I’m sure I’ve missed out on all sorts of other techniques, so do pop down to the comments and let everyone know how you go about writing your finales.

Meanwhile.

Thanks for reading, as ever. If you ever want to chat about your own serial projects, or publishing a regular newsletter, or anything else, paid subscribers to Write More can book in video chats with me. I always forget to mention that.

This weekend was Nor-Con, Norwich’s annual sci-fi and fantasy convention. It’s a cosy and friendly affair and always a lot of fun to poke around the stalls. The organisers manage a good balance of merch and creators, and my favourite thing to do is browse the various artists showing off their stuff.

In attendance this year were none other than Simon Furman and Andrew Wildman, who worked on the 1980s Transformers comic that was quite a seminal work for me. It was the second time I’d met them, having also headed to TFNation in Birmingham back in August. I write more about that here:

I was digging through the archives recently and stumbled upon an interactive fiction project I created as a prologue/teaser for one of my earlier serials. It’s quite a fun thing which you can play for free here:

Working on Tales from the Triverse, my current serial, has been so all-consuming that I’ve not had much time for other projects. Staying focused is crucial for me. I do find myself exceedingly excited now at the prospect of wrapping up Triverse and being free to explore other concepts: comics, more IF, short stories.

I’ll need to figure out how that plays out on this newsletter. Ever since the newsletter existed there have been weekly chapters of Triverse.

Anyway, thank you for coming along for the ride this far. Lots of fun things still to come. Enjoy your week!

Such good points here!

I think that's part of why Joe Abercrombie's The Devils works so well. It's definitely a high-stakes fantasy adventure, and ends in the massive, sprawling battle we've come to know and love (and sometimes hate), but it works because he keeps everything rooted in his characters, and the horror most of them feel at what's happening to them. They never stop being themselves, and so we *care* about what happens

Another thing LotR does really well is establish what the characters are defending and then show them carrying a small piece of the Shire within them, even in the darkest moments. I think Sam's line in the Two Towers sums it up best:

"What are we holding on to, Sam?"

"That there's some good in this world, Mr. Frodo. And it's worth fighting for."

The characters carry that fragile goodness within them, and the Shire makes it manifest. Honestly, it's masterful. But then, I guess we knew that already!

Also, as a small note for future reference: I use they/them rather than she/her

Thanks so much for sharing this, and for tagging me in. It was a great read!

Well reasoned points as always.

Although I disagree on Die Hard. McClain may keep his motivation throughout the movie, but he absolutely becomes a superman during film. As I've joked for almost 30 years, there's a shot at the end of the film of McClain -- who has been beaten, burned, and, oh, yes, walked barefoot on broken glass, before climbing an elevator shaft -- where the camera, at a low angle, trucks in (FYI, moving SIDEWAYS is a "dolly," moving forward/backward is a "truck," and "dolly in" is incorrect terminology) on McClain, tilting up as it does, while he gleams in his sweat and rim lighting. And I hate it. It's his "Superman" shot. You wanna convince me Die Hard stays grounded, show me the version of that shot where his adrenaline buzz fades during the truck, and he passes the fuck out.

Of course, sometimes spectacle slop happens in Act II. I'm thinking of Indiana Jones and the Nuked Fridge Aliens here. There's a moment where Shia LeBeouf is straddling two jeeps on a greenscreen stage and he's hit once-twice-three times in the crotch by plants. It's the exact moment when I stopped caring about the movie and muttered to my date, "This movie needs to have some character scenes soon, because I just don't give a crap about anyone." There was no character scenes until after the aliens do whatever they do, by which point it was too late. No, wait, I did muster up one moment of regard for a character after the crotch shots. Shia swinging with the monkeys. That's when I wanted his character to get killed off.

Sometimes one goes the other way -- not enough spectacle, too many character endings. While Peter Jackson did as well as anyone could do with LotR he really drags the ending out (and cuts the "Scouring of the Shire," but that's a different rant.

Babylon 5 also spends interminable episodes dragging out all the character resolutions, with interruptions for occasional action beats as demanded by the show formula.

Now Simon Jones has, so far, nailed his endings, so I have faith in Triverse.