The movies I remember are the ones that are more varied in their pacing. Terminator 2 is improved immeasurably by the sequence in the desert, when the tension and action drops away, focusing instead on Sarah pondering the role of the father figure. Die Hard intersperses the action with quiet moments of McLane talking over the radio to the cop outside, and crucially shuffles those up to sometimes be funny, sometimes unexpectedly moving.

More bombastic action movies feel more like the kids’ cartoons I watched in the 80s. All-action, all the time. As a young writer it took me a while to unlearn some of those early lessons in storytelling. When my early attempts at stories weren’t working, I thought it was because they didn’t have enough action; it’s more likely that they had too much.

It took me longer than it probably should have to work this out, but in my defence the answer does feel a little contradictory: an action movie is made better by having scenes in which there is no action. A comedy is made better by having scenes which are not funny. A romance is made better by scenes which are not romantic.

This cuts across any story in any medium. As J. Michael Straczynski more eloquently put it recently:

Doesn’t matter whether it’s books, movies, TV, comics — you can’t always be at 100%, because it is exhausting for the audience. Without contrast, the story becomes a sort of grey noise.

Pacing and serials

I write serial fiction, which means putting out a new chapter each week. For a time I felt a real tension between the pacing requirements of the story and the assumption that a serial should always be engaging the readers, to always be pulling them back in, week after week.

Some of this is tactical, in figuring out how and when to have the quieter chapters. There’s a reason the first chapter of Tales from the Triverse is an epic story cutting across multiple characters and locations: it’s designed to set the stage, but also to draw readers in so that the pace can then slow down considerably in subsequent chapters. The different ‘tales’ in the ongoing serial shift from quiet character pieces to all-out action, to more comedic pieces, to social commentary. The pace is always shifting.

There’s a cyclical element to it: a quieter character episode unlocks and enhances a big action sequence, which in turn enriches a character piece, and so on. It’s a feedback loop that keeps the story going.

Cliffhangers

I’ve had people ask me about cliffhangers, and if they’re necessary when writing serials. It’s not easy to come up with a dramatic, dangling plot point every week, but the concern is that without them, readers won’t return. This comes back to the notion of changing it up and avoiding thematic monotony.

A cliffhanger does not always have to be a 1960s-style, can-Batman-escape-the-lava-pit situation. It can’t be that every single week, without becoming repetitive and predictable — at which point the dramatic impact evaporates.

The trick is in having a rich enough tapestry that a ‘cliffhanger’ can take on multiple forms, and operate at different scales. Sure, sometimes you might want to have your lead character hanging off a cliff. But a quiet character moment can be just as pivotal, for readers who are invested in that character. A small, personal revelation. A handful of quiet moments unlocks permission to do something huge and dramatic as a follow-up.

The buckets of pacing

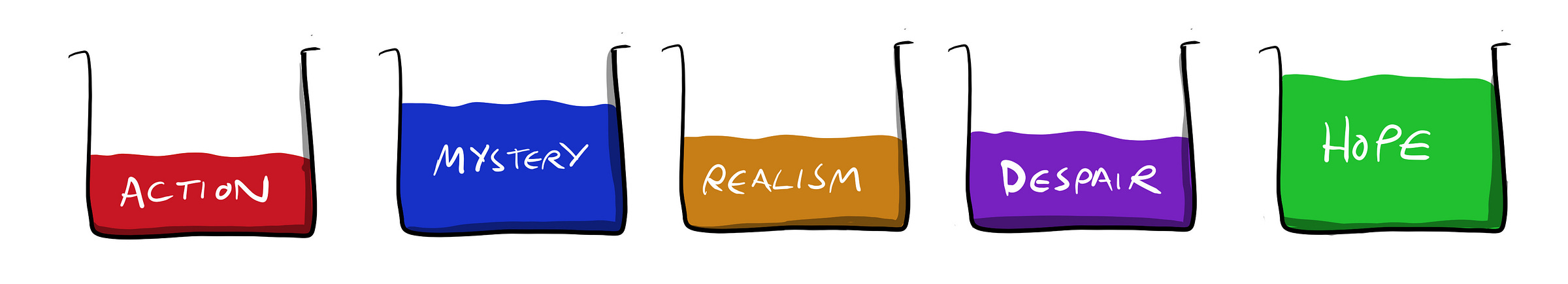

Most of this we know intuitively as storytellers. Perhaps a way to visualise it, if you’re a newer writer, or want to better understand the structure of your own work, or unpick a problem, is as a series of buckets with finite capacity.

PSA to newer readers: I’m known to occasionally go down slightly absurd paths in an attempt to explain my own writing brain. This is one such occasion. (see also: The Story Loom)

You don’t want a bucket to be completely empty, or so full that it’s overflowing. The specific buckets you have will vary depending on your story and your writing style. For Triverse, I might break it down a bit like this as a starting point:

It’s primarily a detective and conspiracy story, hence ‘mystery’ being so high. There are moments of intense action, and while it is squarely in the speculative fiction arena I also try to keep it feeling as realistic as possible. It’s also gritty and uncompromising, hence the despair: but it’s not overwhelming, or nihilistic: hope is there even in the darkness.

The volumes within these buckets shift depending on the current storyline. There may be far less despair in a more comedic story. Sometimes there’s less mystery, and the action ramps up. Sometimes hope dwindles. But if any of these start overflowing, the overall story becomes off-balance. Too much hope will overwhelm not only despair but also realism. Too much action can wash away just about everything else.

Sometimes other buckets will appear, perhaps temporarily: romance, or comedy.

I don’t make a point of drawing buckets instead of writing, I should emphasise. This all happens mostly subconsciously in my head. The figuring out of much of this happens before the writing of the first chapter. But it’s also under continual re-evaluation: has one bucket been too full for too long and is now becoming tiresome? Has a bucket gone dry and needs replenishing?

Ideally, the reader won’t be consciously aware of any of this going on behind the curtain. The end result is hopefully a convincing story that simply works, rather than feeling overly mechanical.

Anyway, there we go. I can add Buckets of Pacing to my slightly silly line-up of pseudo-scientific story analysis tools. 🎉

Meanwhile.

Thanks for tolerating reading.

This one’s coming in a little late in the day so I’ll keep the outro brief.

If you want to see those buckets of mine in action, you can hop into a Triverse story from here:

Tales from the Triverse story index

If you’re looking for my non-fiction writing guides, video tutorials and community discussions, you can find the most popular articles here!

Main thing, really, is to head down to the comments and let me know if I sound utterly mad, or whether this bucket thing might be occasionally useful — perhaps on those occasions when we’re struggling to find the right tone for a chapter, or can’t quite figure out why a story is falling a little flat.

Thanks again! See you Friday for some fiction.

You make some excellent points here, Simon. I agree, and with Mike Miller too about the 'cliffhanger' not having to be a life-or-death situation; just a line that makes people wonder where this is going to lead them - and want to find out, of course. Pacing is a tricky one, and like everything in writing it depends on your audience. Reading through Lawrence Durrell's descriptions in 'The Alexandria Quartet' was a bit of a drag for me as a teenager, even though I appreciated how well-crafted those descriptions were. Likewise, reading Holly Black's Elfhame novels (YA) as an adult felt a bit like being bludgeoned over the head with action-action-action, although they were very entertaining. I'm writing an NYA novel now, so I'm trying to make sure there is quite a lot of action vs. description, but you are absolutely right: none of the buckets should ever be empty.

You’re right about giving readers variation. I’ve seen movies that are nothing but two hour chase scenes and they become boring in a hurry no matter how many cars are wrecked or property destroyed. A break from the action does improve the experience. Writing a novel that can be revamped many times before release would certainly be an easier medium to accomplish this. I think a serial with a weekly release would be a challenge. Thanks for sharing your thoughts and insights.