School holidays scramble my brain when it comes to knowing what day of the week it is, which is why this newsletter is going out rather late in the day. Ahem. Today I’m thinking about handling pacing in your stories when you’re publishing them in a weekly, online format.

The pace of a serialised novel requires some additional thinking over an ordinary book, due to the way most readers will encounter and interact with it.

An ordinary book works like this:

The reader acquires the book

They begin reading the book at the moment of their choosing

They work through the pages from start to finish at their own pace, which could be a single day, a weekend, or several weeks

Readers have full agency and the author has no direct control over how their work is consumed. The chapters of the book are binged, essentially, much like a Netflix series. This tends to be a largely isolated experience, with readers reading asynchronously and discussion therefore awkward due to the risk of spoilers.

A serialised novel works like this:

The author begins serialising their story at a defined pace, such as one chapter per week

Readers access each new chapter, once a week, and cannot read ahead any further than what has been released by the author

There are nuances here, of course. Some readers will only discover the serialised story midway through, at which point they have a choice of reading from that point onwards (which would probably be confusing), or they can go back to the start and catch up to the latest serialised chapter. The model is closer to traditional television, which scheduled episodes. The serialised format forces readers to read in a synchronous fashion, with every single reader consuming the same chunk of story at the same moment. Given the capacity for online serials to reach global audiences, this can create a palpable sense of community around a story. The possibility for group excitement and anticipation is very real.

Once a serialised story is complete, the author can leave the entire thing up for new readers to discover. Those readers won’t really get the serialised experience, instead getting the story in a more traditional, completed book form. It’s a bit like buying the box set of a TV show years after it originally aired.

Pacing

When you have a book (or ebook) in your hands, as a reader you entirely control the pacing of the story. Sure, the author set the template for the story’s pacing within the text, but it’s still up to you whether you race from chapter to chapter, or read a couple of paragraphs an evening before sleep. Whatever pacing was intended by the author is filtered through the reader’s own reading preferences.

A live serial is different, in that the control of pacing returns to the author. If a reader wants to keep reading, they simply can’t if the chapters haven’t been released yet. The speed of consumption is massively slowed, with all ‘live’ readers brought together. Some readers evidently won’t like this model, preferring to read a book at their own pace. In my experience, though, there’s a huge demographic of readers who absolutely love serialised fiction and all of its accompanying quirks.

It does require you to think slightly differently about how you structure the story and the chapters than you might if you were simply releasing it as a complete book. You need to convince your readers to keep coming back every week. The sequence of desired actions is something like this:

Reader reads a chapter and enjoys it

Reader subscribes or follows the book on whatever platform(s) you’re using

The following week, when you publish a new chapter, the reader receives a notification and eagerly returns to read the next part

Steps 1 and 3 are easy. It’s step 2 that is the tricky one, especially if you’re asking for a paid subscription from readers. Your chapters have to be good enough for readers to want to read more, of course, as with any form of writing, but you can also consider timing your plot points to aid with converting readers to subscribers.

Yes, we’re talking about cliffhangers.

Now, these don’t have to be as overt and manipulative as on the old Batman TV series, but if you have some dramatic tension occurring naturally in your story, then it doesn’t hurt to time it so that it reaches a crescendo at the end of chapter. This will create excitement and anticipation for what comes next.

Combine this with an enthusiastic set of readers who are likely to be commenting on each chapter and interacting with each other and you will start to build real momentum in how readers are engaging with your story.

This style of storytelling, with each chapter urging readers on to the next, won’t suit every type of story, which is fine. Think about how TV shows handle this kind of thing: they always want you to come back for the next episode, but each show goes about this in very different ways. You could have a “Next time…” tease at the every end, separate from the text itself. Your story could be so full of momentum that it doesn’t need overt cliffhangers to bring people back.

The other consideration is how this form of pacing will play out for readers who encounter the story later in its life, once its serial run has completed. If you make the cliffhangers and pacing too obviously designed for that weekly hit, it can end up feeling relentless and forced when read back-to-back at the reader’s own pace. That’s a consideration for a later date, though, as you can always edit and reform the story for a subsequent ebook release.

Strangely, in the age of instant gratification, it’s the creation of forced scarcity that makes serialisation so compelling, for both writers and readers. No, you can’t have all the chapters at once. No, you can’t read the next chapter until next week.

Word counts

In a non-serialised book your chapters can be as long or as short as you want them to be, at least theoretically. Once a reader has acquired your book, they can keep reading at their own pace, so chapter breaks are a useful storytelling tool but have no particular bearing on whether the reader will keep reading.

When you’re serialising, especially online, word counts become more strategically important. While there’s no technical limitation to chapter word count, the practical reality is that your readers will be expecting a certain conformity to the experience, just as the expectation with episodes of TV shows is that they will usually run to a standardised length. Even Netflix shows, where they are free from the scheduling and advertising shackles of traditional TV, still maintain half-hour or hourly formats for the most part.

Your readers want to know when they sit down with a new chapter that it’s going to be comparable in size to previous instalments. A drastically shorter chapter will be disappointingly slight and an unexpectedly long chapter could feel like too big a time commitment. The challenging truth is that your serialised novel is competing for a reader’s attention with Netflix, video games, other books, podcasts, radio, sports, movies, all of which are easily available on demand in the 21st century. There is no scarcity of entertainment, so you’d better make sure that your slice is worth their time.

This means that word count becomes a strategic consideration as well as a storytelling consideration. With the three books I’ve serialised I’ve settled over time into a 1,200 word target for each chapter. I never hit that actual figure, with some chapters coming in a little under and some considerably longer, but 1,200 is a very useful average to use in my writing sessions. Looking at serialised works from other authors this does seem to be a good sweet spot.

Anything under 1,000 words can feel too slight. Having waited a week for a new chapter, sub-1k is disappointing, as it’ll only take a few minutes to read. It also doesn’t give you much word space to develop the plot, characters or themes. On the other end, I would put 3,000 words as a maximum. I occasionally tip over the 2k mark, but I don’t think I’ve ever broken 3k. The longer your chapter word count, the more the reader will start to compare it to other things they could be doing. The 1,200 mark I go for is long enough to feel like the chapter has real substance, but is still very easy to consume in a single setting; there’s no challenge to getting through the chapter, regardless of whether the reader is fast or slow. It can be squeezed into a lunch break, a morning commute or over breakfast with a coffee. Start ramping up to 3k+ and your readers are going to have to find additional time to read it, alongside doing the cooking, cleaning, etc etc. Don’t put yourself in that position of competing for a reader’s time.

Equally, don’t feel shackled by these numbers. Consider them a guide, as with everything else in this book, rather than hard rules.

In terms of process, when I sit down to write a new chapter I always set the document word count target in Scrivener to ‘1,200’. This generates a simple and very useful progress bar which sits in the corner of the document, shifting between colours as you close in on the target. Once the bar goes green I know I’ve hit that target - though by that point I’m usually in the zone and don’t even notice. During more challenging writing sessions, though, it’s useful to have that visual mark of progress.

The other benefit to the 1,200 word target is that it is possible to write in one or two sessions. We’re not talking about days and days or weeks of work. A 1,200 word chapter can be written in a week, making it immediately possible to live write and publish as you go. It’s a sweet spot for both the writer and the readers. Having it be a fixed target also creates regularity for you as a writer, so that over time you have an intuitive sense for the pacing of your chapters, as well as how long it will take you to write.

You can also start to ballpark the overall length of your entire story. If you know each chapter is going to average out as 1,200 words, and you’ve decided to feature 10 chapter per ‘arc’, and you want 4 arcs in the book….well, that’s about 48,000 words, so you’re talking a novella. Put 20 chapters into each story arc and you’ve got a novel. And so on. It can help to know - at least in the back of your mind - what you’re getting yourself into.

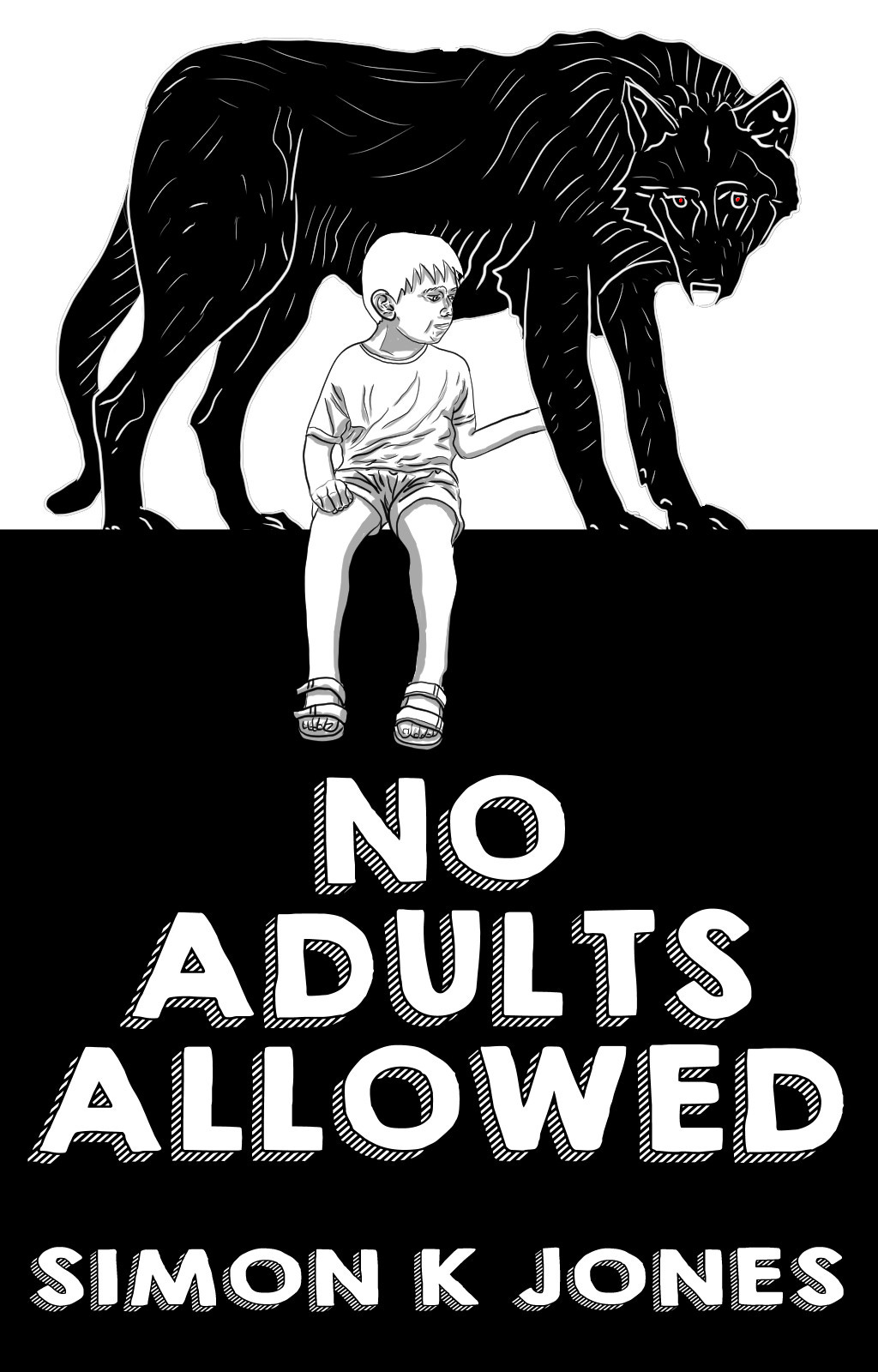

Thanks for reading. There’s still a couple of days to grab some free ebooks in the Strange Tales promo, including my YA novel No Adults Allowed. Check it out here.

Meanwhile, new chapters of my book Tales from the Triverse continue to go out every Friday on this newsletter to early access subscribers. Even if you’re not one of them, the chapters unlock for everyone after 5 weeks. The latest one was the start of a new storyline, so is a good jumping-on point:

You can read from the start here:

See you all on Friday, for the last instalment of 2021.

What is your view, or the general consensus, on serialising scenes as opposed to chapters?

I've written two unpublished novels, one of 110,000 words and the second ending up at 300,000 words.

A quarter way through my second novel, I thought it a good idea to have the protagonist and her story run through every alternative chapter, while the intervening chapters are told from the perspective from someone else, and in most cases loosely linked to the main plot, but mainly running their own sub-plots.

Using Scrivener, I allocated 4 scenes per chapter. Now that I want to serialise the novels, my opening question comes to mind. Will this work, or will the stories lose momentum, if the main plot is dealt with for 4 weeks with a 4 week break while something else is delved into for another 4 weeks and so on?

It all comes together towards the end, and I've created sufficient curiosity at the end of each scene. The thing is a sub-plot might be paced over 4 parts of the 300k book.

OK, so my book is already written, and the average length of my chapters is much higher than 1200. The shortest is 1800, most fall somewhere between 2k and 4k, and the longest is just under 6k. Now the issue I have with this is that I've created the chapters to help structure the story. It's quite complicated, with different settings/timelines and character narratives, so grouping scenes together in chapters and parts helps with reader comprehension. If I were to break down chapters into separate scenes, then I would risk losing the reader. What do you think?