Different types of serial storytelling

Nobody presses the big reset button anymore

Let’s talk about modes of serial storytelling. I mean, to be fair, I’m always banging on about serial storytelling, but today I’m going to attempt to deconstruct different approaches across various mediums.

I have definitely forgotten and overlooked some great stuff. See you down in the comments, where we can all have a collective nerd session.

There’s a lot to learn from how serials have been tackled over the years. The key thing for me is that writing and publishing in a serial form is not the same as just taking a novel and posting each chapter one after another. Serial storytelling works best when the writer structures the narrative purposefully.

Old style serial fiction in the papers

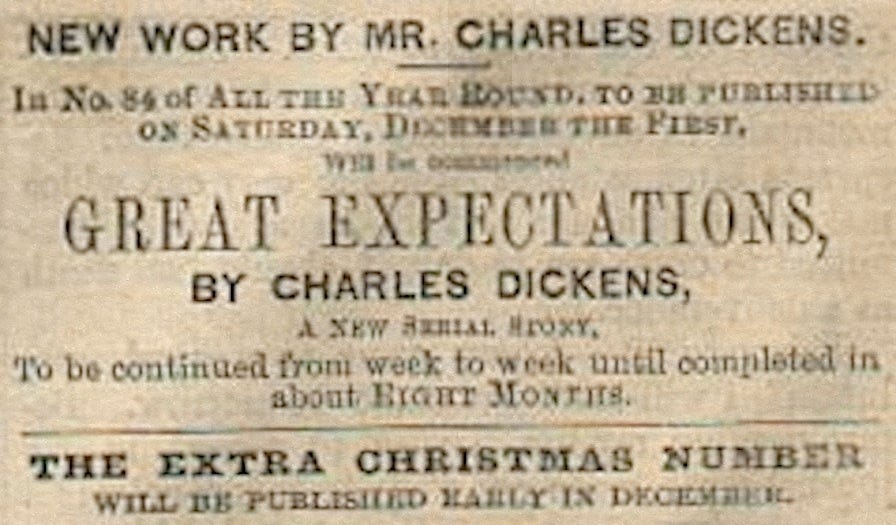

This has been brought up a lot when people write about the ‘resurgence’ of serial fiction. I’m guilty of it. As such, I’m not going to spend too much time on this one, and I’ll try to resist naming the big D. Well, other than in this image:

The short version is that serial fiction used to be very normal and popular, published in newspapers and magazines in the 19th century. You can imagine it being the talk of the town, readers eagerly awaiting the next instalment. The writers could adjust the story over time based on responses from readers, and the finished stories could be adapted into novels.

Key thing is that these were long-form stories, which needed to bring people back each issue.

Next, we’ll fast forward into the 20th century and the emergence of the TV and radio serial. This has evolved and taken on various shapes.

Small screen serials

Serial literature gave way to The Novel. This always strikes me as being a bit of a shame: aside from anything else, serial fiction would have provided a way for a fiction writer to earn a regular income during publication, rather than gambling on the release of a book.

Serial storytelling was still around, of course, and had been embraced by newer forms. Television in particular has explored many variations over the decades.

Big reset episodic

When I was a kid, almost all television other than soap operas was purely episodic. There was a general setup for the show, which would be established in the pilot, and every single episode after that would follow the same general formula.

There would be limited character growth, and any major changes to the status quo would invariably be reset at the end of the episode or forgotten about entirely by the following week.

The premise would be neat and easy to explain in a sentence: the crew of the Starship Enterprise explore a new planet each week. A detective investigates a murder each week. And that’s all you need to know.

The benefits of this are obvious: audiences can start watching at any point and immediately understand what’s happening. Each episode is self-contained and includes enough information to bring new viewers up to speed. This is where the infamous “as you know, Bob” exchange become commonplace, as characters bizarrely reminded each other of things they had personally experienced.

There’s a cosy familiarity to the repetitive structure. The drawback is that the potential for story and character development is kept deliberately minimal.

Infinite soap

I mentioned soap operas earlier. These are in some ways the ultimate form of the serial. Never-ending, internally consistent, and often real-time. Coronation Street has been airing weekly in the UK since its first episode in December 1960.

The show’s creators have produced over 10,000 episodes.

While soap operas have never been my thing, no matter how you look at it we’re talking a major, historical achievement in serial storytelling. Where this becomes especially fascinating is that show’s premise: it’s set on a very ‘normal’ street in northern England, and has updated and evolved in real-time to keep pace with the times. That means the show itself is now a historical record of sorts, depicting the changes in British society from the 1960s to modern day - albeit through a fictional, heightened drama lens.

Some fans of the show will have watched it for their entire life. Astonishing!

Short serials

On the opposite end are short serials. Often adapted from novels into television, previously referred to as ‘prestige drama’ or ‘mini-series’. I remember this being very common in the UK growing up: while US shows would come in at 22 episodes per season, British shows would be around 6 and often one-offs rather than on-going.

In the 80s and 90s Dennis Potter ruled the short-form serial on TV. I still vividly remember his final works, Karoake and Cold Lazarus - even if it seems nobody else watched them. He’s better known for The Singing Detective. (related, this is my favourite news story of the month)

Short-form serials have less time to play with and are therefore more focused in their storytelling: there is little in the way of narrative fat. This means less time to get to know everyone or play with the formula, and the overall ‘feel’ tends to be more literary and novelistic.

This form still exists! More recently I’ve thoroughly enjoyed short-form one-offs like the remarkable Devs and Emily Blunt’s devastating The English.

Long-form continuous

The 90s and 2000s were dominated by US long-form television, coming in at around 22 episodes per season. This was especially the case in science fiction, from the Star Treks and Babylon 5 to Farscape, The X-Files and Battlestar Galactica.

Most of the earlier shows adhered to the ‘big reset button’ approach, with self-contained episodes and little on-going storytelling outside of the occasional fancy 2-parter. This shifted in the mid-to-late-90s, as The X-Files began to weave a long-running conspiracy plot into the individual episodes. It felt like it was going somewhere - although I never stuck with that particular one past season 2.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Write More with Simon K Jones to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.